Typhoon Hagibis, which pummeled Japan earlier this month and caused widespread flooding that killed at least 80, is leading the country to face some tough questions. The disaster has shown that the levees built up over decades along virtually all of Japan’s major rivers may not provide protection from the increasingly powerful storms expected to accompany climate change. Even while construction crews are working to plug the numerous breeches in river embankments, experts and government officials are debating how to prepare for future storms.

Last week, the land and infrastructure ministry announced it was forming a panel of experts to study the embankment failures and recommend remediation options. But experts are also calling for more attention to evacuation planning and long-term measures to encourage people to move off lowlands susceptible to flooding.

Hagibis originated in the tropical latitudes of the western North Pacific Ocean in early October and underwent a period of rapid intensification with 10-minute sustained winds of 195 kilometers per hour as it tracked north and west toward Japan. The winds had diminished significantly by the time Hagibis made landfall on 12 October. Instead of high winds, however, Hagibis brought unusually sustained rainfall, apparently thanks to an accompanying weather phenomenon called an atmospheric river. Still imperfectly understood, atmospheric rivers are narrow channels of concentrated moisture in the atmosphere that sometimes form in association with midlatitude cyclones.

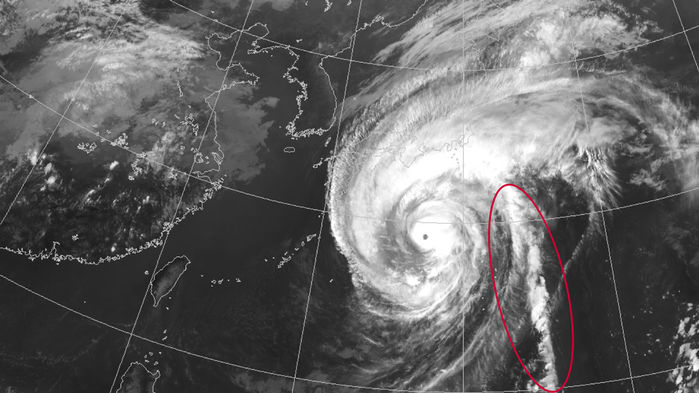

There’s still some debate about whether what was seen with Hagibis meets the definition of an atmospheric river, says Kazuhisa Tsuboki, a meteorologist at Nagoya University in Japan, who is himself convinced that it does. It might be the first time the phenomenon occurs together with a tropical cyclone. Observations by radar and Japan’s Himawari 8 weather satellite, along with simulations, show a wide band of rainfall extending from the tropics to the northeast rim of Hagibis as it landed on central Japan. Tsuboki, who presented his preliminary findings on Hagibis at a workshop on severe weather in Taipei on 15 October, estimates the atmospheric river was carrying twice the volume of water of the entire Amazon and “provided a large amount of water vapor to the northeastern part of Hagibis.”

“I do agree with Tsuboki’s assessment that atmospheric rivers can be an important ingredient in extreme rainfall events like what we saw with Hagabis,” says Robert Rogers, a meteorologist at the Hurricane Research Division of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Miami, Florida.

That extra water resulted in record rainfall. In one calendar day, 922 millimeters of rain fell on Hakone, a town 73 kilometers southwest of Tokyo. The rains caused 55 rivers to breech embankments at 79 locations. In addition to the confirmed dead, 10 or so are still missing, and thousands are still living in evacuation shelters.

This may be the new normal. Hagibis is the fourth major rainfall disaster to afflict Japan in the past 14 months; Tokyo was hit twice in less than 2 months. In July 2018, a succession of heavy downpours in western Japan caused flooding and mudslides that claimed more than 220 lives. Three of the top 10 most damaging Japanese typhoons since 1950 have occurred since 2018, according to a review by the Weather Underground meteorology website.

Climate change is likely causing a detectable increase in the global average intensity of hurricane-strength tropical cyclones, which increasingly occur farther north than before, climate modeler Thomas Knutson of NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey, and colleagues from around the world concluded in a review paper earlier this year.

Mitigating floods from these storms “will only improve if there is an approach with two elements: hardware and software,” says Nobuyuki Tsuchiya, a civil engineer specializing in disaster prevention at the Japan Riverfront Research Center in Tokyo—by which he means flood controls and evacuation planning.

Of the two, bolstering evacuation plans might have the most immediate impact. During the recent storms, far more people were ordered to leave their homes than shelters had room for, says Yukihiro Shimatani, a watershed management expert at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan. The shelters are poorly equipped, he adds, and people with pets or infants and the elderly and infirm often hesitate to evacuate. Governmental authorities have realized that residents in flood-prone areas must be educated to take responsibility for their own well-being, Tsuboki says, but ordinary citizens have limited understanding of flooding. Local media reported several cases of residents who evacuated when Hagibis passed through their area and returned home when the storm had moved on, not realizing that flood waters were coming from farther upstream.

Dredging rivers so they can accommodate a greater volume of water is one measure to improve flood control, Tsuchiya says. Shimatani says the major flood damage occurred where levees have not been upgraded according to existing plans. For the longer term, he would like to see “policies to reduce the population living in danger zones.” Japan’s shrinking population would help make this feasible in the smaller towns along rivers that flow from Japan’s mountains.

But urban populations are much harder to protect. Tsuchiya says there is no room for larger river embankments in the major cities. And significant portions of Nagoya, Osaka, and Tokyo have sunk below sea level, leaving them vulnerable not only to overflowing rivers, but also to storm surges. In September 2018, for instance, a surge from Typhoon Jebi flooded Kansai International Airport, built on a humanmade island in Osaka Bay, disrupting flights for more than 2 weeks and causing major damage. A storm-tossed 2600-ton tanker slammed into and damaged the sole bridge connecting the airport to the mainland, stranding 5000 people on the island for a night.

The bottom line, Tsuboki says: “The Japanese government should consider more seriously the future projection of climate change issued by scientists and take action.”