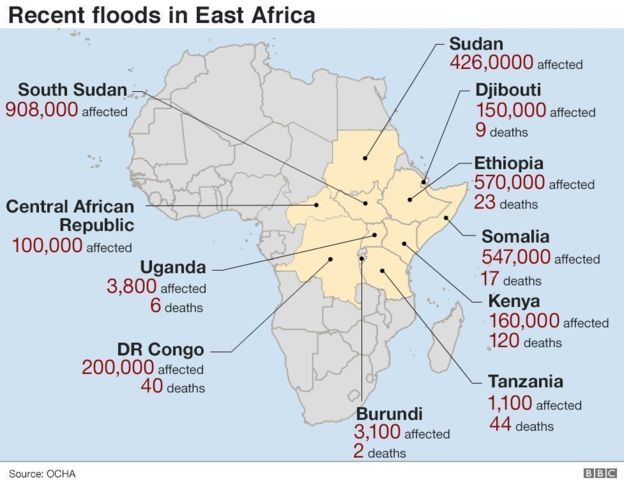

Rain-triggered disasters, including flash floods and landslides, have killed at least 250 people and affected some three million people across East Africa in recent weeks, with about half of the deaths occurring in Kenya.

Homes have been demolished, crops destroyed and roads swept away, hampering relief efforts in far-flung areas.

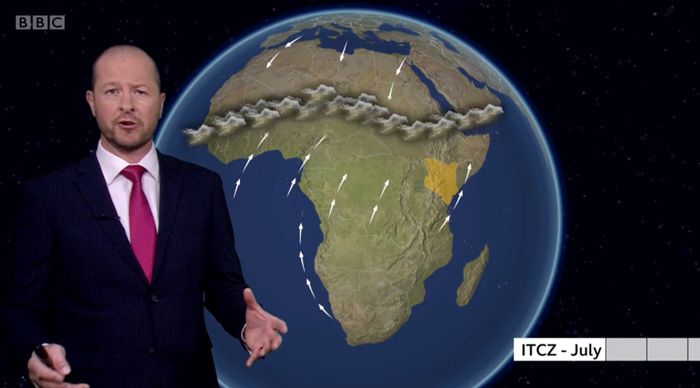

BBC Weather's Darren Bett explains the reasons behind the flooding.

Kenya has two rainy seasons linked to the movement north and south of the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). It is a zone of heavy rain and thunderstorms where north-easterly and south-easterly trade winds meet.

This zone of wet weather moves south over Kenya in the months of October to December and is known as the "short rains".

So, we should expect rain to fall at this time of year in Kenya.

But this is far heavier than usual.

The effects of a warming world on seasonal rainfall in East Africa are unclear. As a rule of thumb (and by the laws of physics), a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour and therefore has the potential to produce more rain.

Media captionKenya flash floods: 'What I saw after landslides in West Pokot'Weather experts say the rains have been enhanced by a phenomenon called the Indian Ocean Dipole which, when positive, can cause a rise in water temperatures in the Indian Ocean of up to 2C. This leads to higher evaporation rates off the East African coastline and this water then falls inland.

The term dipole means two "poles" or two areas of differences. The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) measures differences in sea-surface temperatures between the western Indian Ocean (western pole) and the eastern Indian Ocean south of Indonesia (eastern pole).

The IOD is the Indian Ocean counterpart of the more well-known Pacific El Niño and La Niña.

It is normal to see warming in the western Indian Ocean relating to a positive IOD. This leads to enhanced rainfall across parts of East Africa and droughts across Australia.

The increased temperature and moisture is brought inland by a reversal of the winds near the equator, strengthening the ITCZ and leading to larger and more widespread storm clouds.

This year's sea temperature difference between the western and eastern Indian Ocean has been record-breaking and rainfall in parts of Kenya has been much higher than normal.

The relationship between the IOD and climate change and patterns of rainfall remains the subject of research, partly because the IOD itself was only identified in 1999.

In the short term, the Horn of Africa is expected to be much wetter as a tropical disturbance moves in from the Indian Ocean.

In December the seasonal rains are expected to continue to move south to affect south-west Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi and northern Zambia.

Although the positive IOD is set to decline, because the temperature difference has been record-breaking, rainfall is expected to be greater than normal.

Soil moisture levels are high so only a small amount of rain could have significant impacts.

While there can still be some rain falling in January and February, the next rainy season is March to May.

This time is known as the "long rains" when rainfall is usually more intense than during the "short rains".

History has shown us that the rains are not guaranteed to fall widely every year.

In 2016 and 2017 the "long rains" in areas of East Africa failed and plunged parts of Kenya into a food crisis as cattle starved and crops withered.