The risks of climate change are already impacting investors, with increasingly frequent climate disasters like wildfires, drought, flooding and heatwaves threatening business operations and properties across the world.

Many investors are now choosing to funnel their money into investments that address climate change risk, and asset managers are rushing to meet the demand.

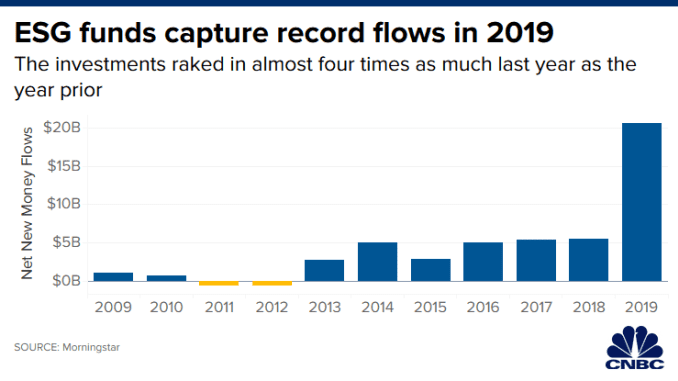

Investors last year put $20.6 billion into funds focused on environmental, social and governance — or ESG — issues, according to Morningstar data, almost quadruple the record the year prior. In the U.S., money managed with sustainable investing strategies now comprises over a quarter of total investment assets under management, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance.

Bank of America also estimates that in the next two decades, there will be over $20 trillion of asset growth in ESG funds, in which climate change investment is a major component.

The focus on climate risk is driven largely by a younger generation of investors who want their money invested with sustainability in mind. They also want to avoid companies with bad track records on ESG issues that could face future fines.

Despite the rise in popularity, sustainable investing isn’t as simple as it sounds. Critics argue that it’s basically impossible to define funds that have an ESG mandate.

SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce, for instance, argues that while the intentions of the investing strategy are sound, slapping an ESG or sustainable label on a fund is subjective and doesn’t mean it’s necessarily in line with an investor’s priorities.

“It seems to be like 2020 is shaping up to be the year of resource misallocation in the name of — but not actually — saving the climate,” Peirce said in a phone interview with CNBC. “If we really want to save the climate, we would allow capital to flow to technologies to solve those problems. That doesn’t involve putting artificial constraints on where capital flows, which some of this trend will do.”

Others argue that the sustainable investing space is essential, but will need to be better defined this year if it wants to continue gaining investor money.

“ESG is inclusive — it helps better measure both performance, but also future potential of different investments through a lens that’s not purely financial,” said Bruno Sarda, the North America president for CDP, an international nonprofit that works with companies to disclose financial risks of climate change on their bottom line.

“Climate change has such strong linkage to financial and operational performance that it needs to move beyond a pure ESG definition,” he said.

The demand for ESG investment options has risen so high that asset managers are scrambling to provide new funds. ESG funds now account for more than $30 trillion worldwide in assets under management. One recent example is the world’s largest money manager BlackRock, which has vowed to make climate change the core of its investing strategy.

BlackRock announced broad changes aligned with ESG, including exiting investments in coal production, introducing more sustainability-focused funds and voting against corporate managers who aren’t making progress on fighting global warming.

Impact investing has been largely embraced by Wall Street. Bank of America has committed $300 billion to sustainable investments over the next decade, and Goldman Sachs has also pledged $750 billion over the next decade to finance and advise companies on sustainable finance. Private-equity firms like KKR, Bain Capital and Apollo Global Management also include ESG offerings.

New ETFs and mutual funds focused on ESG strategies have launched in record number in recent years, and did well in 2019. Over half of sustainable funds rank in the top half of each of their Morningstar categories through November last year. From 2004 to 2018, Morgan Stanley found that the performance of almost 11,000 ESG funds performed similarly to non-ESG funds.

In 2019, top performing diversified sustainability funds, which make ESG evaluation central to the security selection process, included Nuveen ESG Large-Cap Growth (NULG), ClearBridge Sustainability Fund (LCISX), UBS US Sustainable Equity Fund (BPEQX) and Calvert Equity Fund Class (CSIEX).

For fund managers, evaluating specific stocks based on the ESG criteria can be difficult. Nuveen managing director Steve Liberatore, who manages securities on an active total return basis, said that he looks for securities that have direct and measurable social and environmental outcomes, with help from third-party data providers.

“We’re not saying to not to invest in an oil or gas company. But if you are, you want to invest in one that has a historically strong track record in dealing with environmental issues, not one that has a history of spills,” he told CNBC. “By not being a good steward of the environment, it’s putting at risk its ability to secure free cash flow in the future.”

Bank of America’s CEO Brian Moynihan argued this week that interest in ESG among investors will continue to grow, and dismissed concerns that the push towards sustainable investing was a public relations tool.

“All investors are saying, ‘I want you to invest in companies doing right by society,’” Moynihan said at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where climate change was a key theme.

“People say, ‘Isn’t this greenwash?’ Which part of $300 billion do you understand is not greenwash? This is not some small process, it is a business force,” he added.

Research shows that S&P 500 corporations that build sustainability into their goals are outperforming those that don’t, and those that are planning for climate change have a higher return on investment than companies that haven’t. And roughly88% of studies show that firms with social and environmental criteria had better operational performance, according to an Oxford University analysis.

“Across different benchmarks of ESG, companies that take it seriously are financially stronger and get higher financial returns in marketplace,” Sarda said. “If anyone argues that this is a drain on financial performance, the data says otherwise.”

As momentum builds behind ESG investing and analysis of climate change risks on returns, so do concerns over how to define funds that have an ESG mandate. Securities and Exchange Commission regulators have investigated some funds to see whether the claims align with reality, and the extent to which companies adhere to ESG principles.

Peirce said that ESG factors are amorphous and subjective, and therefore the process of determining which companies count as socially or environmentally conscious is “pointless.”

“If you want to judge companies by the ESG metric, that’s fine, but you have to tell people that you’re running a fund for that, you’re only going to invest in companies that meet ESG, and hold to that definition,” Peirce said.

“The idea we need a central decider of what qualifies as good in the ESG world is ridiculous,” she added.

— CNBC’s Pippa Stevens contributed to this report.