The Covid-19 pandemic was unfortunately not the only natural disaster of 2020. There were so many that it’s easy to forget everything that happened this year. Here is a brief sampling of 2020’s weather-related events:

These disasters were deadly and destructive, and several of them nudged records even higher. But while their origins are in nature, humanity’s actions are what made these events truly devastating. From continuing to build in high-risk areas, to failing to evacuate people at risk, to changing the climate, disasters often end up with a far higher toll than they would otherwise. As populations increase in vulnerable areas and with climate change pushing weather toward greater extremes, the risks are poised to grow.

Covid-19 was lurking in the background of most natural disasters this year. Since the pandemic began, efforts to contain it complicated everything from locust control pesticide spraying to organizing camps for wildland firefighters.

And people fleeing disasters faced extra challenges as they tried to maintain social distance in shelters that tend to force people into close proximity.

“The threat of Covid-19 transmission means we need to be additionally vigilant in protecting both our emergency response teams and the people they are helping,” said Oxfam Philippines’ Country Director Lot Felizco, in a statement about Typhoon Goni in November. “The loss of critical facilities, vulnerabilities from lack of adequate food and shelter, poor conditions in evacuation centers, and ongoing displacement means we have to ensure response actions do not increase Covid-19 risks on top of other disease outbreaks.”

At the same time, disasters made it harder to contain the spread of the coronavirus, which has already killed more than 1.8 million people around the world. The pandemic also devastated the global economy, and many local disaster responders saw budget cuts and layoffs just as their communities needed support the most.

“Yes, it’s a health crisis,” said Aaron Clark-Ginsberg, a social scientist who studies disasters at the RAND Corporation. “It’s also an economic crisis, and it’s a social crisis.”

Disasters in 2020 also compounded when extreme weather struck repeatedly. Louisiana, for instance, saw a record five major storms make landfall this year, including Hurricane Laura, the strongest storm to strike the region in 150 years.

Meanwhile, back-to-back wildfires across the western United States not only destroyed homes and businesses, but cast smoke over huge swaths of the country, turning skies orange and making breathing the air as bad as smoking a pack of cigarettes in a day. That dirty air in turn worsened risks for Covid-19, a disease that afflicts the airways. “Exposure to air pollutants in wildfire smoke can irritate the lungs, cause inflammation, alter immune function, and increase susceptibility to respiratory infections, likely including COVID-19,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The events this year showed that disasters aren’t singular events, but overlapping and intersecting phenomena. In the future, disaster planners will have to better account for how many things can go wrong at once, and that areas may not have time to fully recover from one catastrophe before the next one strikes.

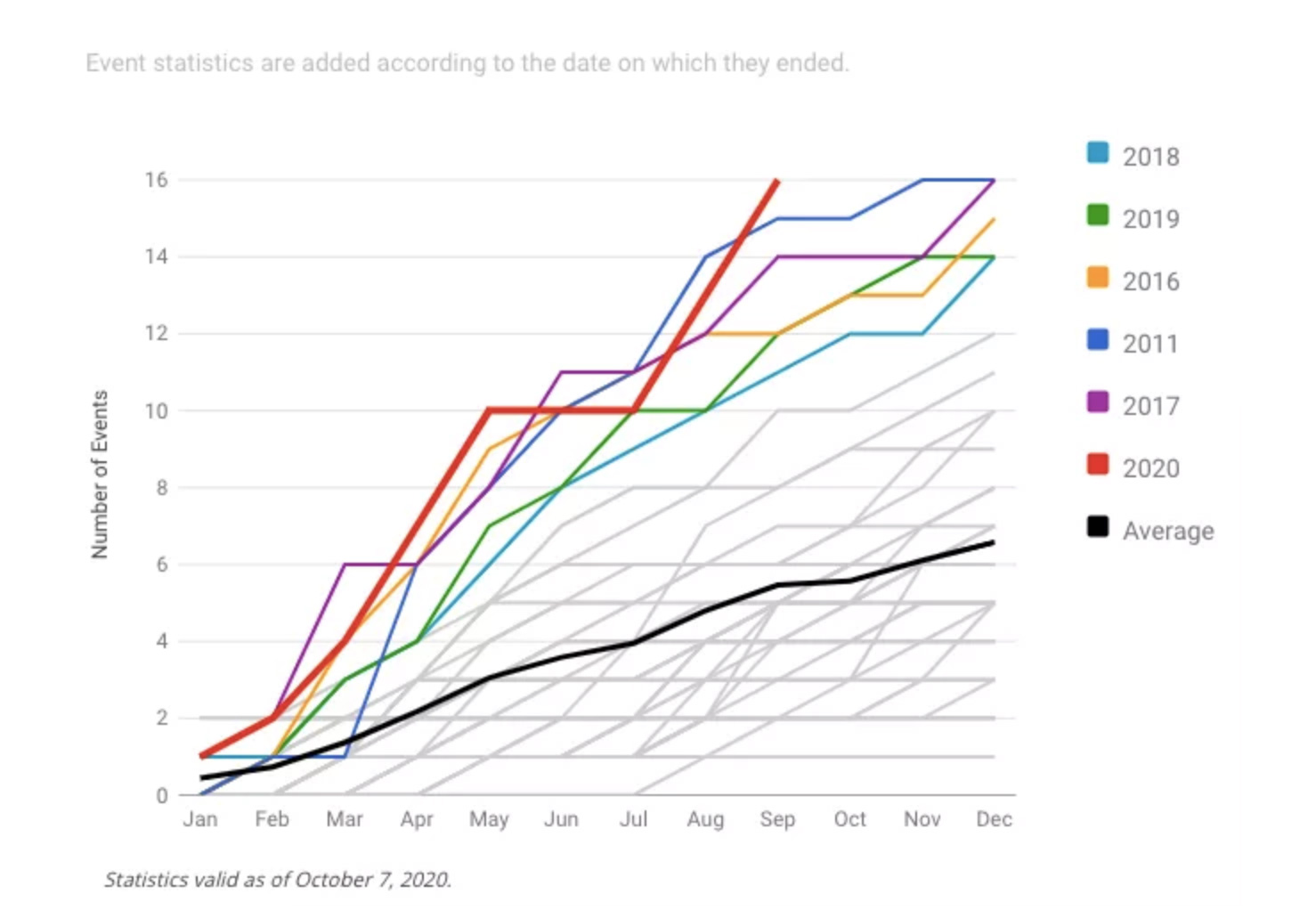

Around the world, more than 40 disasters led to at least a billion dollars in damages each. The United States in particular set a record for the number of billion-dollar disasters this year, with at least 18 such events. These include not just hurricanes and wildfires, but droughts and heat waves. Hurricane Laura was one of the costliest events of the year for the US, with upward of $12 billion in damages.

The dollar amounts, however, don’t tell the whole story. Poorer people are often more seriously harmed by storms, floods, and fires. But because their property is valued lower, the price tag can understate the scope of the destruction. Damage to facilities like offices and factories also often show up as more costly than damage to people’s homes. So the places with the costliest disasters aren’t necessarily the places that are suffering the most.

At the same time, the economic harms of disasters are mounting in part because more people and property are in harm’s way. For example, about 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometers of a coastline. About 40 percent of the US population lives in a coastal county. The number of people in these areas is growing, bringing with them more homes, offices, and industries. That means that when storm surges and hurricanes arrive, they’ll extract a higher toll.

Similarly, people in the western United States are continuing to build in fire-prone regions. That not only raises the destructiveness of wildfires when they burn, but it also increases the likelihood of igniting those fires in the first place, since the vast majority of wildfires are ignited by human activity. One study found that 645,000 homes in California will be in “very high” wildfire severity zones by 2050, based on current trends.

All the while, people are changing the climate. Emission of heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels is amplifying the raw ingredients of many of these disasters — air temperature, ocean temperature, and rainfall — and pushing them to be more destructive. Climate change doesn’t “cause” disasters, but it makes it likelier for them to reach greater extremes.

Scientists in recent years have gained a better understanding of how to attribute extreme events to climate change caused by humans. For example, a study from the World Weather Attribution research consortium investigating Australia’s bushfires found that climate change increased the likelihood of the conditions that fueled the blazes by at least 30 percent.

Climate change is also shaping how these disasters unfold. One climate change signal that’s been emerging in recent hurricanes is rapid intensification, which NOAA defines as a gain of 35 mph or more in wind speed over 24 hours. That was visible this year in Hurricane Laura, which surged from Category 2 to Category 4 strength over several hours.

Between 1982 and 2009, the number of Atlantic tropical storms that have rapidly intensified increased significantly, in part due to human-caused climate change, according to a 2019 study in the journal Nature Communications. Climate models also show that rapid intensification will increase as average temperatures rise.

It’s clear, then, that the impacts of disasters stem from forces of nature as well as humanity’s decisions. However, because people are driving many of the factors that make extreme weather so devastating, people can also take steps to reduce these impacts. That can take the form of relocating away from high-risk areas, building seawalls and protective infrastructure, and investing more in disaster management so communities can recover faster. And over the long term, reducing greenhouse gas emissions will help avert the most extreme disaster scenarios.

But the impacts of the disasters this year will linger for a long time as people look to rebuild their lives and cope with the trauma. “Disasters change people, they change communities, and they change societies,” said Clark-Ginsberg. That means the shadow of 2020 will likely stretch well into 2021 — and beyond.