For people who live along the sandstone shoreline of southeastern New Brunswick, constant erosion and rising sea levels are a fact of life. But as developers push to build closer to the ocean, experts say it’s time to better protect the coast.

Steve Glidden and Pete LeBlanc of the Cap Bimet Residents Association worry a proposed five-storey, 92-unit apartment complex next to the coast could contaminate their wells.(Pierre Fournier/CBC)

For people who live along the sandstone shoreline of southeastern New Brunswick, constant erosion and rising sea levels are facts of life.

As developers push to build closer and closer to the ocean, environmental experts say it’s time for the province to strengthen the rules that protect the coast.

University of Guelph’s Robin Davidson-Arnott describes New Brunswick’s coastal areas protection policy as “not very strong,” while Mount Allison’s Jeff Ollerhead says, “New Brunswick is not at the progressive end of the spectrum.”

Both warn it is taxpayers who will be left to pay the long-term costs of disappearing beaches, flood-damaged homes and risky rescues for first responders.

I’ve seen lots of stupid things in my life, but this is a really bad one.

– Robin Davidson-Arnott, University of Guelph

Concerns about building along the coast were recently raised in Cap Bimet, a 20-minute walk at low tide from Parlee Beach, where a Moncton developer has proposed a five-storey, 92-unit apartment building with underground parking within 30 metres of the shoreline.

People who live in the tiny community say the relatively large building will change their quiet way of life, but Davidson-Arnott says his concerns come from a scientific point of view, not an emotional one.

The proposed new apartment building, depicted in grey, overlooks the Northumberland Strait and would sit within 30 metres of the coast.(EIA Registration/Brinkley Investments)

“I’ve seen lots of stupid things in my life, but this is a really bad one,” the professor emeritus in the department of geography, environment and geomatics, said of the proposal.

“The hazard of putting up a five-storey building [with an] underground parking lot — it’s a really, really bad place to put something with underground parking.”

He worries that disturbing the soil and excavating into the sandstone bedrock so close to the shoreline will risk contamination of the wells that supply water to the existing 200 cottages and condominiums in the community.

“You may actually lose most of the water and disturb the aquifer that’s there,” he said. “And certainly if you’re putting down a basement, you have to be pretty good about not letting nasty things in the basement seep into your water system because it’s just above sea level.”

The building site for the proposed apartment building in Cap Bimet can be seen here, to the east of the two swimming pools at the top of the photo, and to the north of the large building which is a condominium. It is the former site of Paturel’s fish plant.(EIA Registration/Brinkley Investments)

Davidson-Arnott worked with Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources as part of the team that wrote the shoreline management policy and technical guidelines for the Great Lakes.

He said the rules there wouldn’t allow any new construction in such an area to have a basement. In fact, he said, all new construction on top of a bluff where the shoreline is retreating has to be moveable.

“If we were in an area like this, subject to flooding, you would probably be saying no new houses can be built with any kind of basement,” he said. “They all have to be built on a pad that is raised above the foreseeable flooding limit. And thirdly, you might want to have them all built so that they could be moved off of the area.”

“That’s one of the issues that happens in an area like this with sea level rise … ultimately things become uninhabitable, and then you’re left with the task of removing all the stuff that’s there.”

University of Guelph professor emeritus Robin Davidson-Arnott helped to write the regulations about coastal development in Ontario, and said New Brunswick’s rules need to be stronger.(Sumbitted by Robin Davidson-Arnott)

New Brunswick’s coastal areas protection policy, which was last updated in March 2019, lays out regulations for two “protection zones.” The first, known as Zone A, is the most sensitive and includes beaches, dunes and marshes.

According to the policy, “Due to the extreme sensitivity and the very high risk of danger/damage from storm surges, fewer development activities are permissible in Zone A.”

The policy says “erosion control structures,” which include rock armour along the coast, is acceptable as long as it isn’t within a coastal marsh, and the applicant has “demonstrated that there is evidence of erosion and a resultant risk to infrastructure.”

Rock has been installed along the coast in Cap Bimet in an effort to protect the land from erosion. The proposed five-storey apartment building would overlook this rock bank.(Vanessa Blanch/CBC)

Dominique Bérubé, a coastal geomorphologist with the Department of Natural Resources, said the average cliff recession rate at Cap Bimet has decreased with the installation of rock armouring.

It was 0.20 metres per year between 1944 and 1971, but just 0.10 metres per year between 1971 and 2001.

Bérubé said based on the provincial database, the average cliff recession rate along the Northumberland Strait is 0.28 metres per year under natural conditions.

Davidson-Arnott cautions against coming to the conclusion that rock armouring can slow the recession or erosion rate permanently, and said there are long-term, negative side-effects.

“If you haven’t had a big storm for five or six years you think, ‘Oh, well, everything’s OK,’ but over that period stuff has been eroded.”

He said piling large rocks and boulders or building retaining walls along the shoreline causes underwater erosion and the entire coast eventually “gets undercut.”

“The underwater erosion continues,” he said. “And so it gets deeper, and when it gets deeper, the bigger waves can reach the shore.”

Jeff Ollerhead, a professor of environment and geography at Mount Allison University, said rock armouring of the shore is already causing the loss of beaches. Along much of the coast, there is no longer enough sand at high tide for beach goers to lay out their towels.

Ollerhead said deeper water means bigger waves crashing against boulders and that means more loss of sand, dunes and wetlands. He worries New Brunswick will end up with cement retaining walls to keep the ocean back — something he refers to as the “New Jersey-fication” of the coastline.

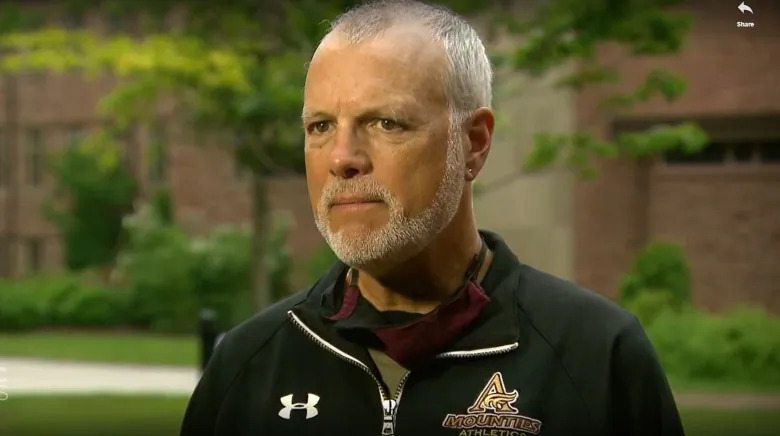

Jeff Ollerhead, professor of environment and geography at Mount Allison University, says protecting the coastline is in the collective interest of all New Brunswickers. The cost of future flood damage will be paid for by taxpayers.(CBC)

“You can find places on the New Jersey coastline where there’s nothing but a cement wall — that is the coast now. It’s just a cement wall … there is no beach, there is no sand dunes, there are no creatures that don’t enjoy living on a cement wall because that’s what you get for a coast.”

The second protected area outlined in the New Brunswick policy is Zone B, which is a “coastal lands buffer” that runs 30 metres inland from the shoreline.

In Cap Bimet, the new apartment complex would be built within this 30-metre buffer zone, something Davidson-Arnott said shouldn’t be permitted.

In Ontario, rather than a fixed line for setbacks, it is a moving line. Davidson-Arnott said most developers don’t like it, but that line is “recalculated by the conservation authorities every five to 10 years.”

It is also recalculated every time someone applies for a building permit based on the rate of erosion, or recession.

“In Ontario, the regulations would say that you have the 30-metre setback, and then you have 100 times the annual recession rate. So if you’re recession rate is about 0.3 metres a year, that would be another 30 metres on top of that.”

In the case of the proposed development at Cap Bimet, if the regulations were the same as they are in Ontario, the apartment building would have to be set back approximately 60 metres from the shoreline.

“Because we assume a 100-year lifespan. So 100 times the average annual recession rate is to allow you to have 100-year use of your property.”

Ollerhead believes coastal development is something every New Brunswicker, not just those who live along the water, should care about.

“When large flooding events happen or coastal storms, the government comes in with government relief, financial aid for those who suffered damage,” he explained. “So there is a collective public interest in this.”

In Caissie Cape, many beaches now disappear at high tide with the continued use of rock armour to protect the coast.(CBC)

Davidson-Arnott understands the pressure local governments feel to increase their tax base, and that it can be hard to resist adding tax dollars to a community, but he said it’s critical that planning boards and local leaders take a long-term approach.

He remembers a big storm in 1985 in Longpoint, a 40-kilometre-long spit in Lake Eerie. He compares the road into Longpoint to the road into Cap Bimet and believes it should serve as a warning.

“There were eight or nine cottagers who were still there during the storm, and they had to try and rescue these people — the cottages were being washed into the marsh,” he said. “So it’s not only endangering the lives of people who are in there, but it’s endangering the lives of people who have to come in and rescue them.”

Davidson-Arnott said the bottom line is that a building must be designed to withstand the elements that will “come at it” in the long run, and the proposed apartment complex at Cap Bimet is an example of why coastal regulations must evolve.

“You have to take into account flooding, sea level rise and coastal erosion, and from my perspective there’s no site in this area here that would warrant putting up a five-storey building.”