COVID-19 has emptied office building and shuttered stores, crippling America's downtowns. But if climate scientists are right, a slower moving foe — flooding — could pose an even greater risk, threatening to drown the nation's commercial real estate.

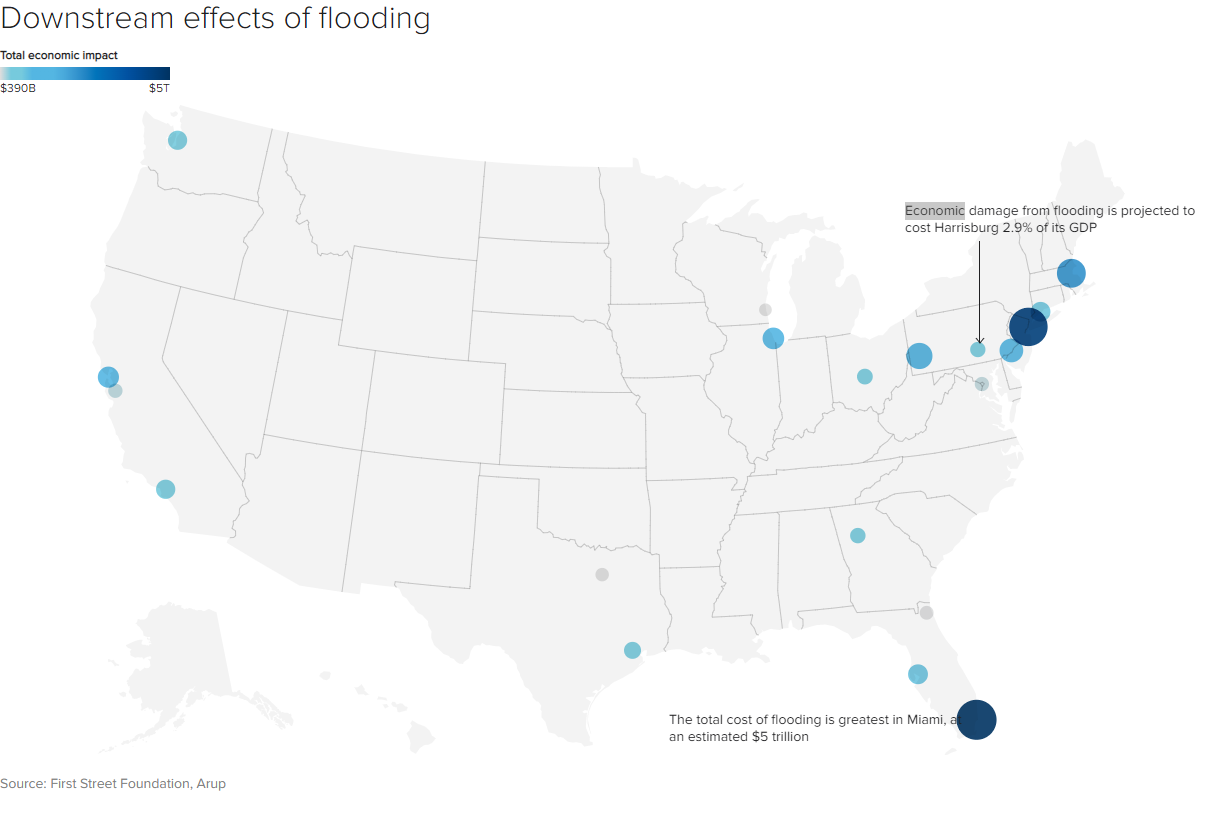

The rising waters are already endangering hundreds of thousands of commercial structures, according to a first-of-its-kind report released this month. More than 700,000 apartment buildings, malls and office complexes face flooding risks in 2022 severe enough to impede business access, according to the analysis from the nonprofit First Street Foundation and engineering firm Arup. For businesses, the total downtime could reach 3 million days, while the economic impact of closures would approach $50 billion a year.

"American businesses and local economies face much more uncertainty and unpredictability when it comes to the potential impact of flooding on their bottom line than they may realize," said Matthew Eby, executive director of the First Street Foundation.

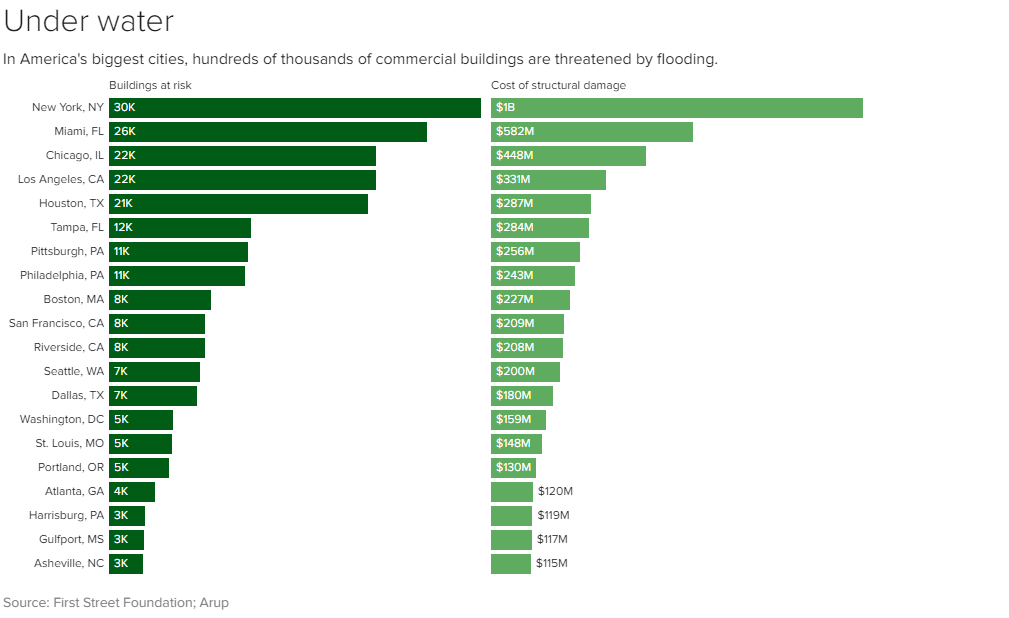

New York City, home to the nation's costliest real estate, is at greatest risk, according to the analysis. Nearly 30,000 buildings in the Big Apple are vulnerable to flood damage in 2022, with the potential cost for structural repairs topping $1 billion. Miami, which regularly floods at high tide, ranks No. 2 — more than half of the commercial structures in the Florida city are at risk of flooding, including several major landmarks such as the Freedom Tower and the Pérez Art Museum Miami, First Street found.

But coastal regions aren't the only parts of the U.S. that could see more flooding. Inland cities including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; Chicago; and St. Louis also are under siege.

"The biggest cities, and the downtowns in particular, tend to be very, very close to water," noted Jeremy Porter, First Street's head of research.

Many of these older cities developed along waterways, which were essential for transport, food and eventually industry. But their aging infrastructure, combined with rising waters and more intense storms associated with climate change, means that many of these historic downtowns are in peril.

In Pittsburgh, which sits at the confluence of three rivers, more than a third of the commercial buildings face a flood risk today, First Street and Arup found. That includes one of the city's best-known buildings, the PPG Tower — a glass-sided castle that's appeared in movies such as "Inspector Gadget" and "The Dark Knight Rises." In Boston, 1 in 5 commercial buildings are at risk of flooding; in Philadelphia, it's 1 in 10, the analysis determined.

Flooding is already the most expensive and the most common natural disaster facing U.S. homeowners, costing $150 billion over the past decade, according to the Federal Emergency Management Administration. But until recently, information on flood risks to businesses has been harder to come by.

"Nobody's done this on a national [level] in a way that's scalable," Porter said. "All the data that exists on floodplains for commercial buildings tends to be private payouts."

To analyze the business risks, First Street and Arup used a peer-reviewed flooding model that First Street developed and applied it to common types of commercial buildings, such as malls, office high-rises, apartment buildings and general-use commercial properties. Then they came up with a model for how flood depth translates into structural damage as well as reduced usage.

The researchers found that even small amounts of water — as little as a few inches — could have destabilizing effects on a region's entire economy.

For a moderate amount of flooding — say, a foot — the damage to a building is often relatively limited, requiring the owner to replace electrical outlets on the first floor and some of the building's insulation, for example. That amounts to relatively small expense for a 30-floor office tower. But if the month in which those repairs are being done results in a building's lobby being inaccessible, that makes flooding a hit not just to a business' productivity but also potentially to the local economy.

"The downstream impacts of those closed days isn't just the product that they're not producing or the employees that aren't being paid. It's all of the other items that would go into that — from the supply chain to their business, the products that those folks would buy, and the overall business stimulus that happens from that company's economic activity," Eby said.

Climate change is likely to exacerbate the already significant effects of flooding, according to climate experts. Arup already has seen "a huge spike" in requests from businesses worried about their climate-change exposure, said Ibbi Almufti, who leads the firm's resilience practice.

He hopes that making flooding data available to businesses will encourage owners and developers to retrofit their buildings to withstand severe weather. Preparing for a wetter world could mean a range of changes to typical commercial properties, from installing swales and rain gardens to elevating electrical infrastructure so it's higher off the ground.

"If critical equipment is in the basement or on the first floor, it's much more vulnerable to flooding than if it's in a third-floor utility room," Almufti told CBS MoneyWatch.

The heightened focus on flood-proofing America's commercial districts raises another critical question: Who will pay for it?

Most building codes don't require taking climate change into account. And most developers, eager to make a profit, won't do it unless it's required. As more information on flood risks emerge, businesses will likely need to prepare on their own, hardening some locations and abandoning others.

"Information about where the risk is greatest — and people are going to realize it sooner or later — is going to start to drive some property values down," Almufti said. "What I hope is that, conversely, it starts to incentivize developers and others to build more resilient, because that is going to attract more premium and more people."