On 27 February, Karl Sprogis and his wife Jill spent most of the night anxiously monitoring flood height data from Australia's Bureau of Meteorology.

Their town, Lismore, was caught in the catastrophic floods that submerged southern Queensland and northern New South Wales in February and March. Those floods have become the most costly in the nation's history, according to the Insurance Council of Australia.

The latest flooding to hit Australia came at the weekend when Sydney was hit with torrential rain. Thousands were told to evacuate their homes and roads were cut by deep water.

Back in February, perched on a hill the Sprogis family home was safe, but the couple were worried about their downtown physiotherapy business. It was purposely located on the second floor but even that was not enough.

From the water-height charts they could tell the office was going to be inundated, but it was too late to save anything, the authorities had already issued an evacuation order.

"We could have put things up higher at that time, had we known, but we didn't," says Mr Sprogis, who had been at his practice the night before.

"I even left my new laptop on the office desk, thinking, well, [the water has] never been in here before so it won't come in."

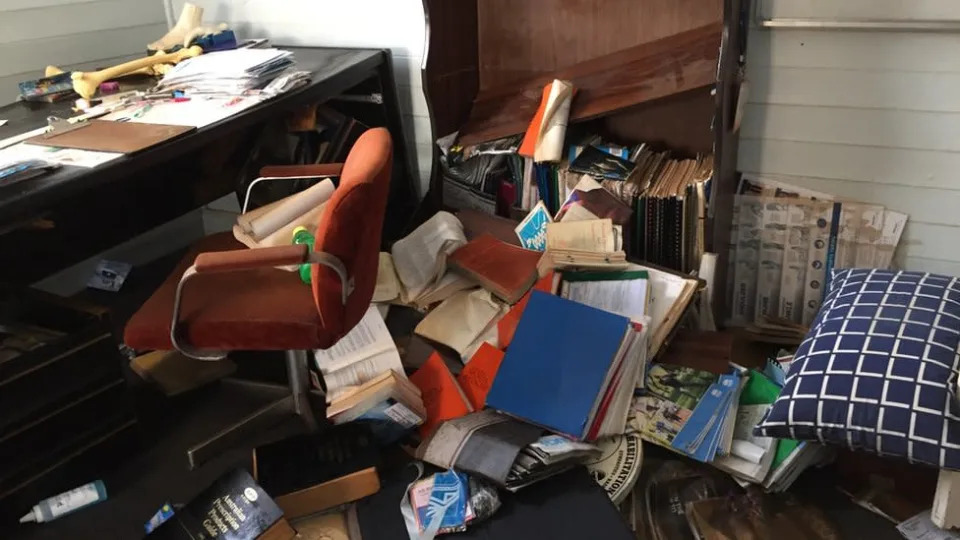

By the following day, his practice was 1.8m underwater, files, records and equipment all damaged or lost.

Meanwhile in New South Wales in Gibberagee, children's book author Candy Lawrence watched as 2,000 copies of her books were sucked into the deluge.

Ms Lawrence had been carefully watching government flood warnings and gathering supplies, anticipating that nearby roads would be cut off, as often happened when the area flooded.

But, like Mr Sprogis, she was not expecting water to sweep through her property and that of her neighbours, some of whom had to scramble onto their roof to escape the fast-rising floodwaters.

"I feel like the world is pretty much ending, so why bother educating children?," she says, referencing her destroyed book collection and the terrifying new weather patterns.

Like thousands of others caught in the disaster, Mr Sprogis and Ms Lawrence would have liked more warning. So why wasn't there a better system, which could alert them in real-time if their properties were in danger?

Juliette Murphy, a water resources engineer specialising in hydrology and flooding asked this question after watching her friend's house in Brisbane flood over the roof peak in 2011. The question came up again after she moved to Calgary, Canada, and witnessed a similarly devastating flood in 2013.

Ms Murphy knew that during the Brisbane and Calgary floods, hydrology forecasts had predicted where rivers would peak at certain bridges, but she realised it wasn't enough.

"If you aren't a hydraulic engineer [who is able] to translate that flood height into an impact to properties - your personal property, your car - it can be very challenging," she says.

Ms Murphy also notes that static flood maps - including those that chart one-in-100-year floods - are also expensive, and can take days, or weeks, to produce. This makes them more suited to development planning and infrastructure design applications, rather than emergency planning and management.

"I was thinking, there has to be something more," says Ms Murphy.

She began dedicating her evenings and weekends to looking for a solution, which eventually led her to co-found FloodMapp with web developer, Ryan Prosser.

With a significant research and development investment, FloodMapp was launched in 2018.

FloodMapp's technology can rapidly forecast water levels to map floods before they happen.

It does this by ingesting huge amounts of historical data (including things like rainfall and ground saturation levels) and uses artificial intelligence to accurately model the way water will behave.

The software also uses information about land features and river systems to work out how a flood will affect different areas. The company claims its models can run 100,000 times faster than traditional techniques.

An added benefit is that the resulting models can refresh hourly using real-time river sensor data and rainfall forecasts.

The technology is not available to individuals, instead it is being integrated into services offered by government agencies in Australia and the US, to better understand floods before, during and after they happen.

Researchers at the University of Melbourne's Department of Infrastructure Engineering are taking a similar approach, understanding that speed is key for emergency planning.

Like Ms Murphy, flood modeller turned researcher, Dr Wenyan Wu, is looking at ways to simulate flood levels over time, at speed, using machine learning techniques. Importantly, this is being done Dr Wu says without compromising accuracy and without costing the earth.

The availability of accurate real-time data that can be interpreted at a property-specific level is a huge part of the challenge, but being able to disseminate meaningful data to the public is also key.

As Dr Wu says, "If people's collective comprehension [of flood risk] doesn't improve, you will not actually improve the situation."

Even the concept of a one-in-100-year flood is widely misunderstood. (It means a flood event has a one in 100 chance of happening in any given year, as opposed to there only being one major flood every 100 years.)

That's where companies like the Australian-based Early Warning Network (EWN) come in. EWN sends opt-in SMS (text messages), email, landline and app push alerts to residents and businesses in at-risk areas, typically via insurers, councils and other government agencies who have signed up to their services.

Flood alerts are primarily based on data collected and distributed by Australia's Bureau of Meteorology.

However, as operations manager Michael Bath explains, EWN has a 24/7 team of human severe weather forecasters (all of whom have an understanding of threats from their experience as storm chasers). This team assess the warnings, eliminate duplication, and send geo-targeted alerts, using custom-made software.

This ensures people receive clear and localised information.

"If you've ever had automated warnings from weather agencies before, [you'll know] they can be very repetitive," says Mr Bath. "If you automatically send that to residents, they just get really annoyed with it and tune out."

Mr Bath, Dr Wu and Ms Murphy all agree that ultimately governments need to adopt these systems and technologies, and make planning decisions about whether future development should be permitted on floodplains and whether buy-back schemes are warranted in high-risk areas.

However, in many cases, moving entire communities or renovating properties at scale using flood-resistant materials is not practical in the immediate future, given these measures require significant funding and political will.

"We need something today, right now, because we are living on floodplains, and emergency warnings and alerts fill a critical role to improve safety, to save lives and prevent damage," says Ms Murphy. "We have to work together to build a safer future."