Accessible, potable water is critical for human health, stable human societies and sustainable ecosystems – thus, water shortages have the potential to lead to political and social unrest. More than 780 million people – about 11% of the world’s population – do not have access to clean, safe water. Even more worrisome is the estimate that about half of the world’s hospital beds are filled with people suffering from a water-related disease.

Water resources are under stress and increasing demand is adding further pressure, while climate change is increasing variability in the water cycle, inducing a greater number of extreme weather events, reducing the predictability of water availability and affecting water quality. In turn, this cascade of consequences threatens sustainable development, biodiversity and the enjoyment of the human right to water and sanitation worldwide.

All around the world, billions of people also feel the impacts of climate change through water. The frequency of water-related disasters is on the rise due to the increase in the intensity of natural events such as storms, high winds, heavy precipitation and dry spells. Floods, droughts, landslides, glacier lake outbursts and storm surges are impacting lives and infrastructure in coastal zones and mountain tops, in arid plains and deserts, along river banks and in floodplains. The poorest and least developed are the most vulnerable.

Risk assessment, proper planning and mitigation are the cornerstones of any National Meteorological and Hydrological Service (NMHS) measure to reduce flood risks. Timely forecasts and warnings must be produced at the regional, national and local levels and be communicated through the appropriate authorities in language that they understand.

IDMP will be supported by climatological and hydrological prediction capabilities, water resources management, the Global Hydrological Status and Outlook System (HydroSOS), Regional Climate Centres (RCCs) and Global Data-processing and Forecasting System (GDPFS). Drought risk management should be undertaken by Members and through WMO regional climate centres.

WMO supports resolving the equation of water demand for human consumption, irrigation requirements, water availability and potential water storage and provides advice to optimize rainfed and irrigated agriculture. The water-energy-food nexus should be considered as well.

WMO Global Hydrological Data Centres take the lead in this area. They will benefit in this task from further developments in the Global Hydrometry Support Facility (HydroHub), especially its Innovation Hub and Quality Management Framework, the World Hydrological Cycle Observing System (WHYCOS), and the Meteorological, Climatological and Hydrological Database Management System (MCH). These are all essential for the wise management of water resources.

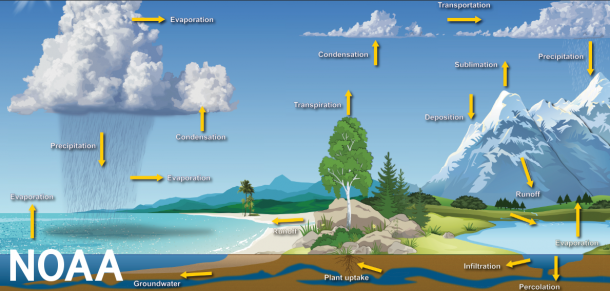

Operational hydrology would benefit from an improved understanding of the impacts of various stressors on the hydrological cycle, in support of closing the water balance.

Further development of WMO initiatives, such as WHOS, HydroSOS and the Global Cryosphere Watch, matched with other international efforts, should support a fully operational World Water Data Initiative and enable local and global assessments of the availability of water resources.

Hydrological information should be available at the time and space necessary to optimze operational water resources management in support of water-dependent sectors and for planning and adapting to transient environmental conditions, particularly those associated with climate change.

A new partnership is needed to support this ambition, including existing links to the Global Environment Monitoring System-Water (United Nations Environment Programme), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and other relevant stakeholders.