This week:

In Montreal, during an unusually hot stretch earlier this month, Friederike Otto took a few hours to walk up Mount Royal and explore the city.

Otto, an internationally renowned climate scientist, was in Montreal to accept an honorary doctorate from Concordia University and give a lecture about her work. That it was unseasonably warm during her time in the city's concrete-laden downtown was impossible to ignore.

"I really was conscious about it because it was clear that Montreal is not a city built for these temperatures," Otto said in an interview after her talk.

"On a day like this, it becomes so much, so obvious — how stupid the world we've built is in terms of causing the problem, but also then making it really hard to to deal with this."

As one of the founders of World Weather Attribution (WWA), Otto has made understanding the connection between climate change and extreme weather her life's work. Climate attribution studies have helped underscore the dangers of an ever-warming world, and are being used in courts to hold governments and corporations accountable for their failure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Increasingly, Otto has also tried to understand how communities — especially in the poorest parts of the world — can better adapt to heat waves, floods and storms.

In the aftermath of an extreme weather event, WWA uses climate models to quickly analyze relevant data to determine to what extent climate change made the event more likely.

WWA's research is designed to be published quickly, and help shape public discourse while a weather event is still in the news. (Given the time constraints, the studies are not peer-reviewed, but they are based on peer-reviewed techniques.)

In the past month alone, the group has released research linking climate change to severe heat in Asia, rain storms in the United Kingdom and flooding in East Africa.

Last year, it determined that climate change more than doubled the likelihood of the conditions that led to Quebec's record-setting wildfire season.

In her Concordia talk, "From Extreme Weather Attribution to Climate Litigation," Otto highlighted a cross-border lawsuit launched by an Indigenous Peruvian farmer, Saúl Luciano Lliuya, against the German energy giant RWE.

In a case based largely on attribution science, Lliuya argues that the German company is partially responsible for the threat that the glacial runoff poses to his home. The plaintiff is seeking a sum equivalent to RWE's overall contribution to global climate change of 0.47 per cent. (The case remains before the courts.)

In another milestone case, a group of 2,000 elderly Swiss women successfully argued that their government's inadequate efforts to combat climate change put them at risk of dying during heat waves.

Last month, Vermont became the first state to enact a law requiring fossil fuel companies to pay a share of the damage caused by climate change.

More and more, legal challenges rely on attribution science to make their case, according to Otto. "This is not a panacea; it won't solve all the problems," she said.

"But with some of the cases that have recently been successful, it could maybe really make a change."

In recent research, Otto has highlighted how such events disproportionately affect the most vulnerable in the world's poorest countries.

"What turns a weather event into disaster has often very little to do with the weather event itself. It's totally driven by vulnerability and exposure," she said.

Otto cited the example of a torrential rainstorm, analyzed by WWA, that descended on Greece and Libya last September. In Greece, 17 people died. In war-torn Libya, where there was no early warning system in place, and dams and other infrastructure hadn't been well maintained, roughly 4,000 died.

"The same weather event can have vastly different impacts in different circumstances," she said.

Speaking after her lecture, Otto said her team can only do so many studies, and given the rise of extreme weather, it can be difficult to keep up with demand.

In the future, she envisions a larger network of scientists, including government departments, working in this field. Her native Germany, she pointed out, is developing an extreme weather attribution system. Environment and Climate Change Canada is also working on a system to quickly analyze the link between weather events and climate change, but there's no timeline for when it will be in place.

"It's still only our team who does this rapidly. I would really want that to change," Otto said.

— Benjamin Shingler

New Brunswick has developed one of the country's most comprehensive websites detailing the risks of coastal and inland flooding. It's an important development, according to realtors, homeowners, insurers and experts. From the sudden, catastrophic rainfall in Edmundston in 2023, to the January supertide that washed onto properties in St. Andrews, intense weather patterns are raising the stakes for property owners all across the province. The insurance industry argues that N.B.'s flood mapping will be an important tool for assessing flood vulnerability as climate change increases the risks of weather-related property damage. CBC is taking a deep dive into the mapping tool — how it works, its usefulness, its shortcomings, who's using it and what it can reveal for the prospective homebuyer hoping to avoid a washout.

— Harry Forestell

A mining company is looking into repurposing one of its shuttered gold mines in Nova Scotia to create a hydro energy storage system and solar farm.

Atlantic Mining wrapped operations at the Touquoy gold mine in Moose River last year, and announced this week it has a new idea for the site.

The subsidiary of Australia-based mining company St Barbara is teaming up with Halifax-based renewable energy firm Natural Forces for a feasibility study into what they've dubbed a "renewable energy hub."

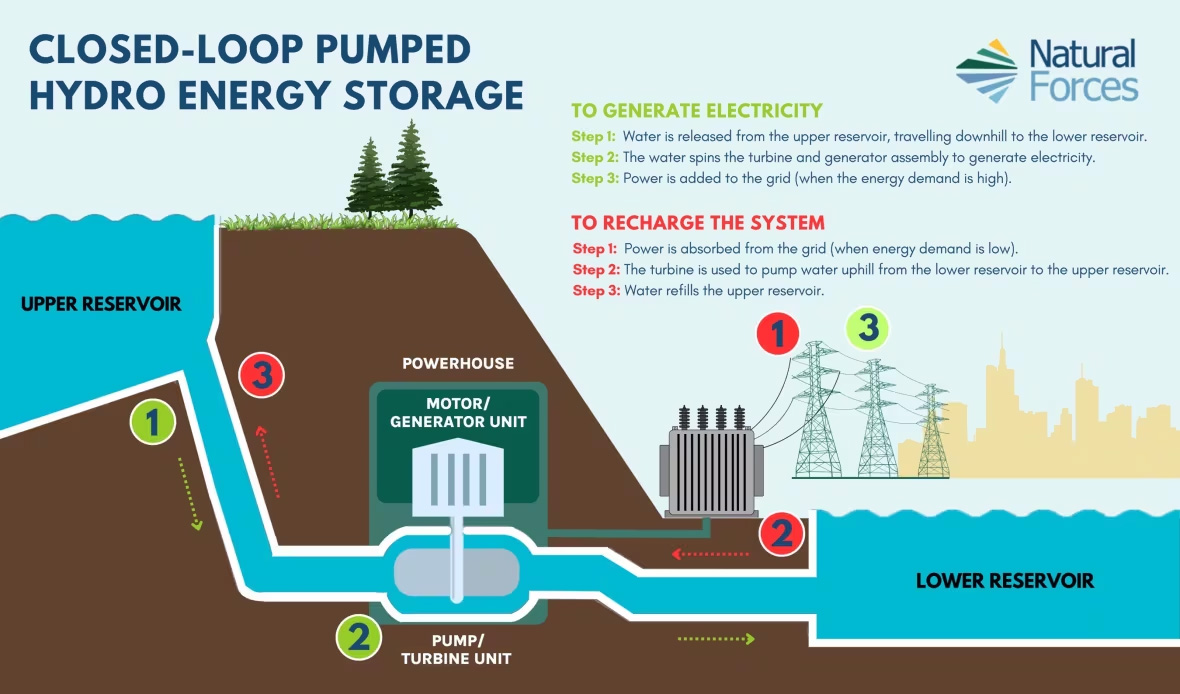

Using the mine's open pits, it would feature what's known as a closed-loop pumped hydro energy storage system, which uses water in an elevated reservoir to act as a natural battery.

The system would include two connected water reservoirs, one higher than the other, filled by naturally accumulating rainfall.

When demand on the power grid is low, the system would take power from the grid to pump water to the upper reservoir. When energy demand is high, water from the upper reservoir would flow through a turbine back into the lower reservoir to generate electricity and feed the grid.

"It just seems like a really excellent way to repurpose an existing pit," Amy Pellerin, director of Canadian development at Natural Forces, said in an interview.

"They've already created the elevation difference and they've already created a reservoir."

Pellerin said the feasibility study will also explore building a solar energy project, which would connect to the provincial grid, on the mine's waste rock pile.

A spokesperson for St Barbara said the mine's tailings facility would be topped off and remain separate from the hydro system.

Andrew Strelein, managing director and CEO of Atlantic Mining, said in a news release that this approach is part of the company's commitment to sustainable development.

"Since closing Touquoy, we have been looking at potential alternative land uses as we move into mine reclamation phase," he said in the release.

Approval from the provincial government for the Touquoy gold mine included a requirement for Atlantic Mining to carry out reclamation after closing.

Pellerin said reclamation of the site will be considered in the feasibility study.

A spokesperson for the provincial Department of Environment and Climate Change said Atlantic Mining has not yet approached the department about the project, and it would need more information from the company before assessing what new environmental approvals might be needed.

Environmentalist Karen McKendry said innovation around greening the electric grid is a good thing, but she's wary about this idea because of Atlantic Mining's "tarnished track record so far in Nova Scotia."

McKendry, who is the senior wilderness outreach co-ordinator for the Ecology Action Centre in Halifax, pointed to charges levied against Atlantic Mining for breaches of environmental laws.

The company was fined $10,000 and ordered to pay an additional $240,000 in financial penalties after pleading guilty to federal and provincial environmental charges relating to its gold mining operations on Nova Scotia's Eastern Shore.

"Compared to some other companies in Nova Scotia, they haven't been the best stewards of the environment," McKendry said.

She said she wants to see more details about how exactly this project would fit into the reclamation of the Touquoy mine.

— Taryn Grant