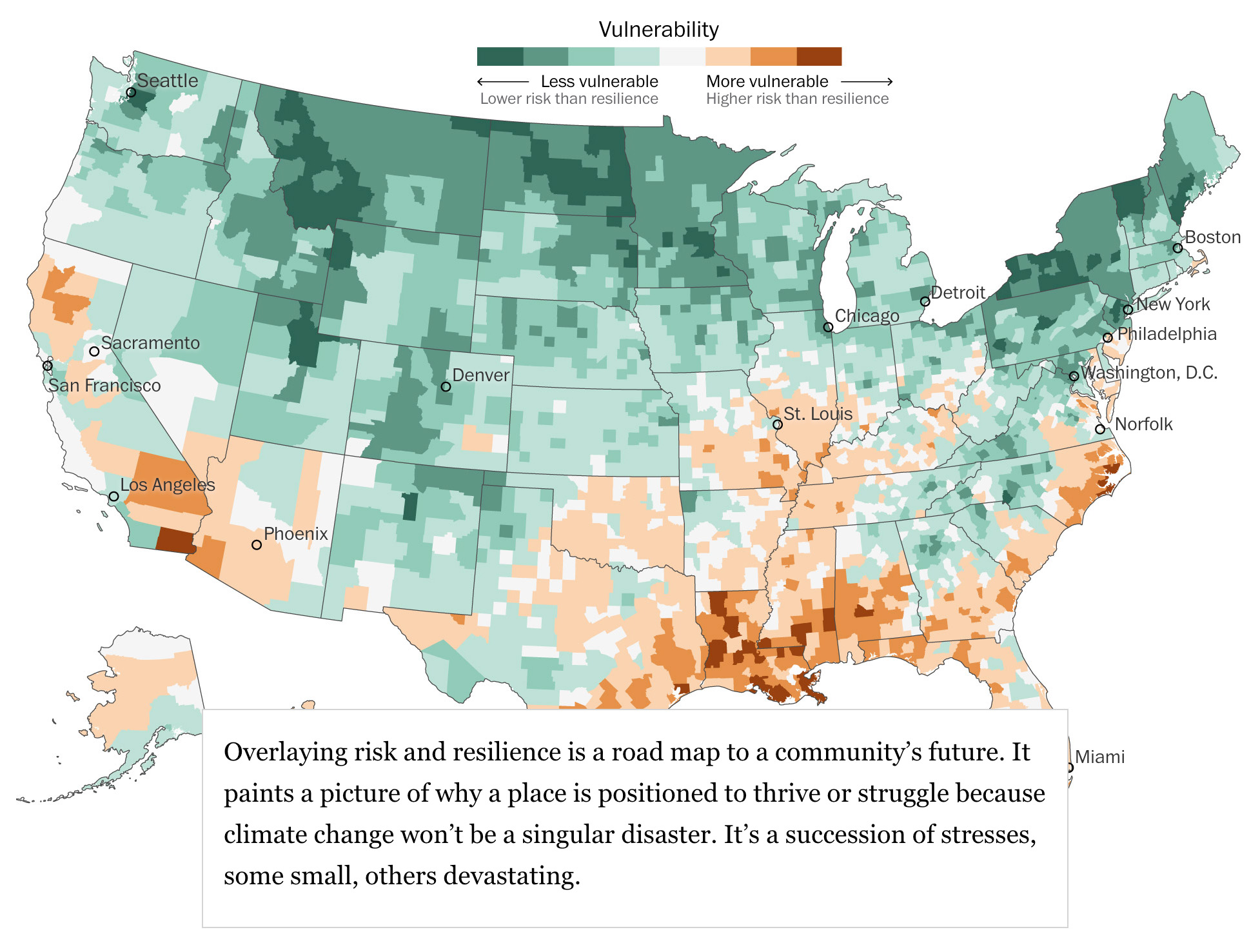

Most people think about good schools, safe streets or desirable jobs when considering where to live. As climate risks inexorably rise, how well your community bounces back from a climate-related disaster — or even a bad thunderstorm — will begin to weigh more heavily on the value of your home.

Imagine a house high up on a hill. It may seem safe from flooding. But the streets around it become impassable during storms or even high tide. Getting to the grocery store is difficult. As extreme weather worsens, insurance rates rise. Some carriers stop issuing policies — or cancel them. Even if the house on higher ground is safe, property values could fall, reducing tax revenue needed to rebuild and protect the city. A downward cycle could ensue.

“The individual shoulders the risk of the community,” said Brian Stone, a professor and director of the Urban Climate Lab at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

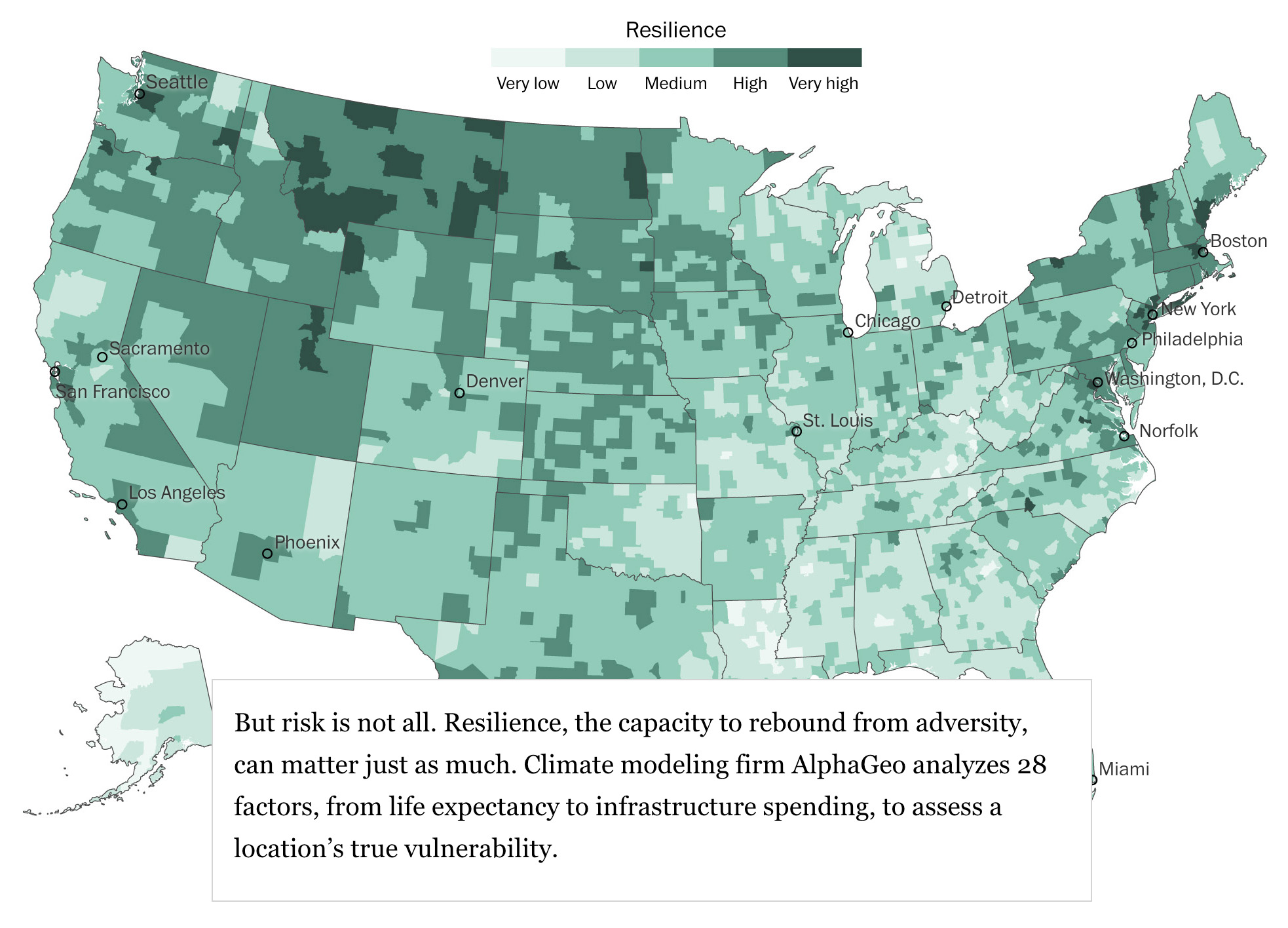

Yet communities can also offer protection. It’s not just risk that determines the value of a home, argued AlphaGeo’s founder and CEO Parag Khanna: “It’s how resilient you are.” Resilient cities hold their value and appeal to new and current residents, enabling even risky places to thrive.

While there’s no perfect way to measure resilience, there’s a growing body of data to draw from. AlphaGeo helps real estate, insurance and financial firms predict how global climate models translate into local impacts, and how those risks might be offset by factors on the ground, from a city’s finances to how old the buildings are.

We teamed up with AlphaGeo to reveal where and why communities appear best positioned to recover from adversity. We looked at the nation overall, as well as two high-risk, high-resilience communities — the flood-prone military town of Norfolk and California’s Placer County, which is threatened by wildfire.

And we built the tool below so you can compare your city’s risk and resilience scores, and judge its vulnerability in a volatile climate.

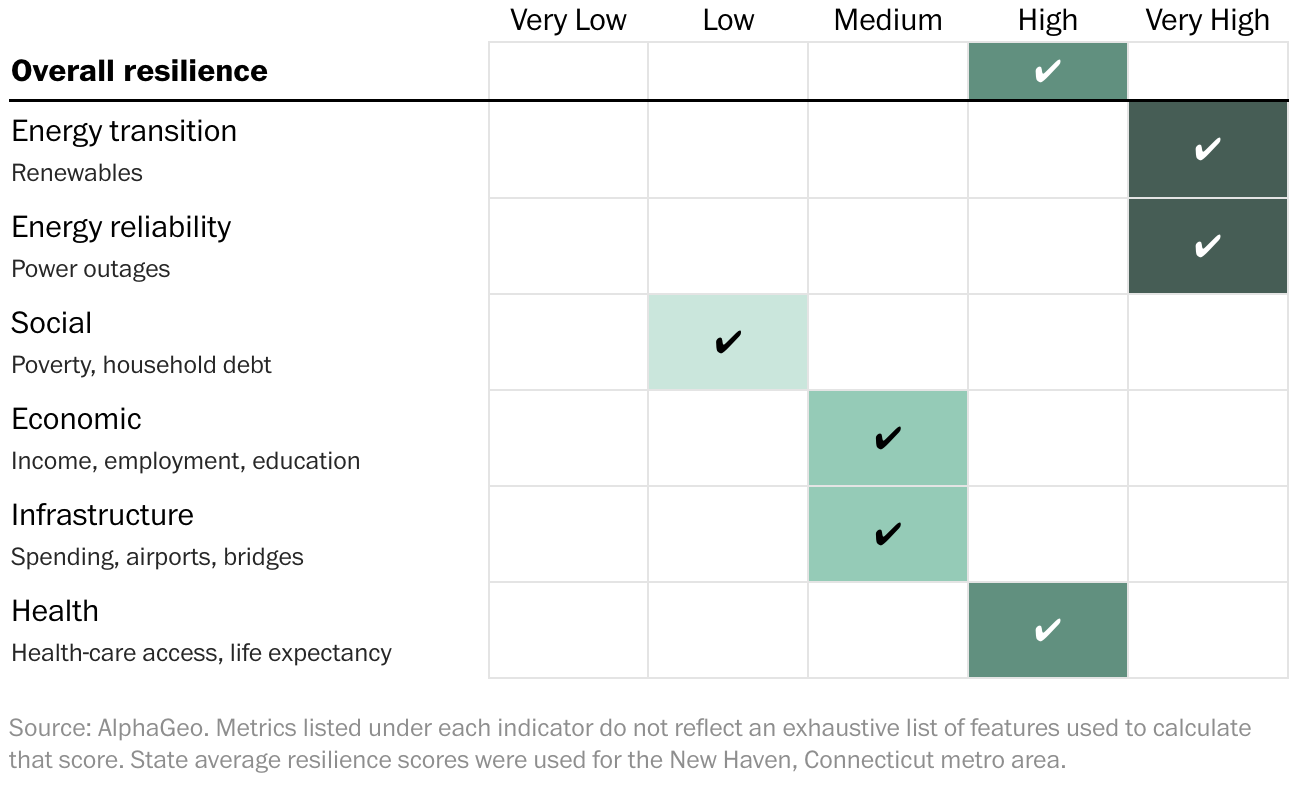

You can think about resilience as four broad categories: infrastructure, economic strength, good governance and social cohesion. Each reinforces the other. Physical infrastructure — such as a reliable electricity grid or a new seawall — protects people and job-creating businesses and, by extension, tax revenue. AlphaGeo looks at income inequality and household debt to assess if a community is tightly knit. Well-functioning local governments also help. The firm estimates how different factors, like a good stormwater system management during a downpour, could offset a community’s risks.

Your city ranks high for resilience. Here’s a breakdown of the individual indicators:

This is only a snapshot — and an incomplete one at that. The precise nature of resiliency will shift over time, as scientists collect more data about what factors matter most. But it’s one way people can glimpse the future of where they live.

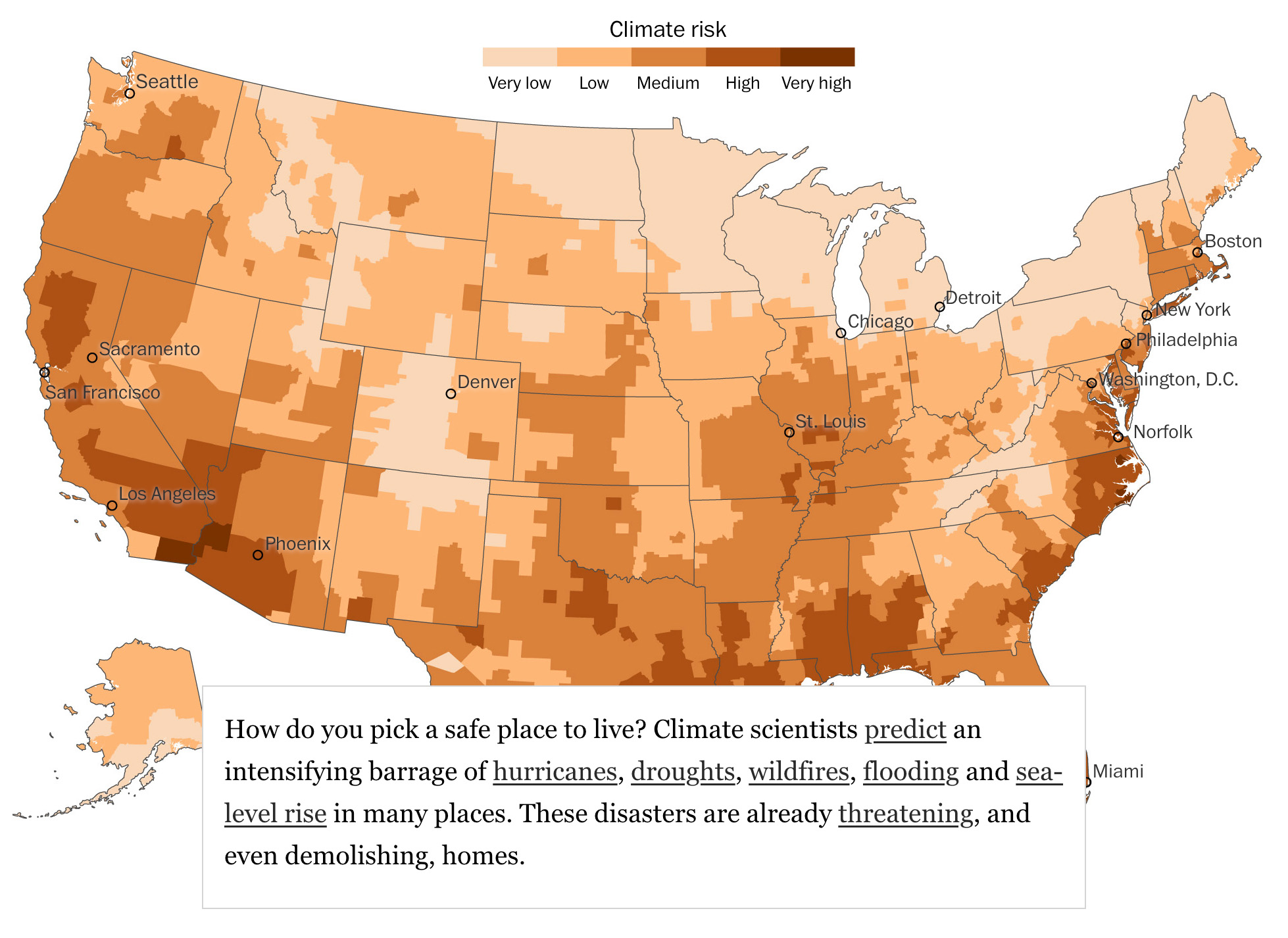

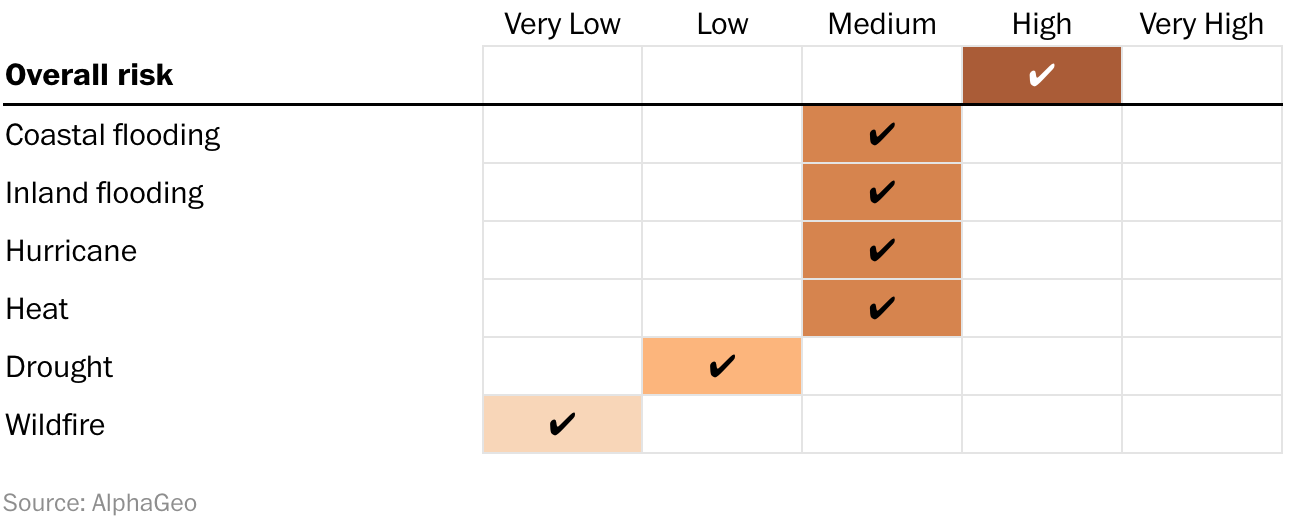

Risk is not just a once-in-a-century disaster. It’s also everyday exposure to extreme weather, wildfire smoke, rain bombs, hail and inland flooding. Even “climate havens” like Asheville, North Carolina, suffer disasters like Hurricane Helene.

“No place is particularly safe,” said Alice Hill, a former Obama administration official and co-author of the book “Building a Resilient Tomorrow.” “But some places are safer than others.”

Your city ranks high for risk. Here’s a breakdown of the individual risks:

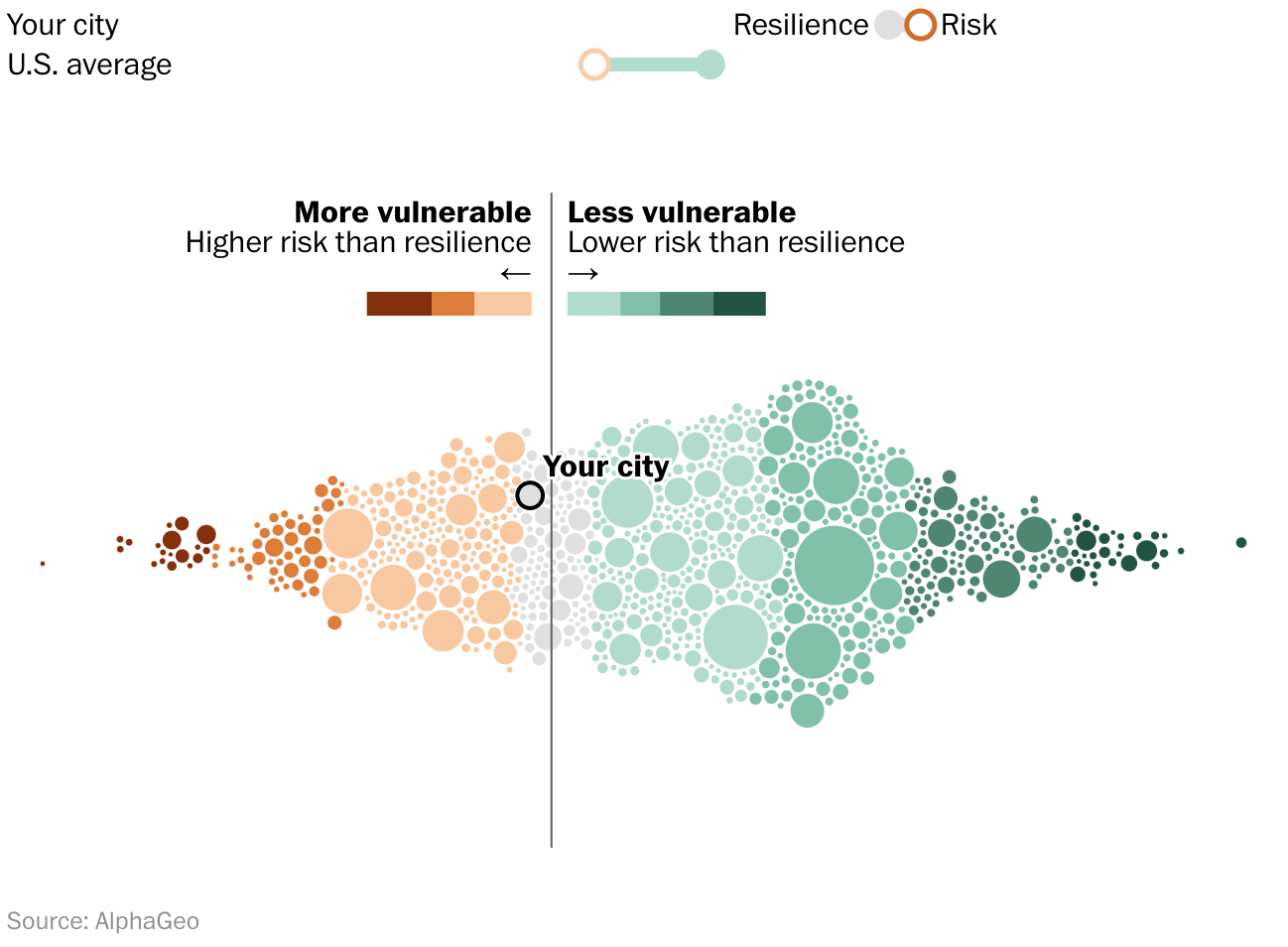

High resilience, however, can offset high risk.

Take the Netherlands. The Dutch organize their society around flood protection. To push back the Atlantic Ocean and control riverine flooding, they’ve invested billions of dollars into thousands of miles of dikes connected to dams and floodgates. Roughly 20 percent of the country’s territory used to be part of the North Sea.

Cities are following in the Netherlands’ footsteps. New York City is installing floodgates around Manhattan and turning vulnerable coastlines such as Staten Island’s Oakwood Beach into storm surge buffers. Boston will spend more than $1 billion to protect its 47-mile coastline. Inland cities from St. Louis to Duluth, Minnesota, are redesigning their drainage systems for a wetter world.

Your city is as resilient as it is risky. Here’s where it stands among all counties in the country:

Cities can expect the cost of coping with climate change to keep rising. “Calculating the risk is easy,” said Lauren Sorkin, co-founder of the nonprofit Resilient Cities Network, which helps cities cope with climate impacts. “Managing the risk is the hard part.”

Two communities, nearly 3,000 miles apart from each other, show what it may take to thrive in the face of coming adversity.

Lionell Avant wants his last days to be on Norfolk’s Westminster Avenue. He bought the white house with two porches, just a few blocks from where he grew up, in 2004, and raised his children there on a half-acre of pines and oaks along the Elizabeth River.

But he’s worried about the water.

Avant, sporting a graying beard and baseball cap, took me around the side of the house where the driveway slopes down. “We’ve lost countless things over the years to floods,” he said, pointing to a small garage. “I see the water flows by everybody else. But it all just settles down here.”

A few years ago, his house was placed in flood zone “AE,” a high-risk category. His mortgage lender forced him to purchase flood insurance for the first time. His neighbor, who received the same designation but couldn’t afford the bill, moved.

A storm grate now collects standing water when it rains, rusty from saltwater below. “It’s not going down anymore,” he said. “So something’s changed.” He hadn’t considered climate change before, but looking across at his neighbor’s vacant house, doubt crept into his voice. “I’m going to lose my house, too,” Avant said. “That feels like that’s the plan.”

When flying over Norfolk, the city appears like an outpost of dry land surrounded by water. Flooding has always been a problem here. It’s now sinking into the ocean faster than any other place on the East Coast due to land subsidence and rising seas.

In less than 20 years, some streets here will begin flooding twice daily at high tide, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science predicts. If nothing is done, experts predict storms and rising waters will inundate much of Norfolk, leaving Avant and many others underwater.

The city is battling two enemies: massive storms off the Atlantic and rising seas. An event like Hurricane Sandy, warns the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, could send a devastating wall of water crashing over the city. But even during normal storms, city engineers say, rain often flows into pipes filled with water. Old tidal creeks, which became dumping grounds, are reemerging.

To respond, Norfolk officials have mounted one of the country’s most aggressive climate resilience efforts. The city began integrating sea-level rise as part of its planning and zoning in 2013, publishing a detailed plan through 2100 three years later. In 2023, it signed an agreement with the Army Corps for a $2.7 billion project that will protect core areas of the city with roughly nine miles of flood walls and levees, 11 tide gates and 10 pump stations.

An earthen berm — a raised area of land often made from gravel — can help direct runoff water and protect properties from flooding.

Where the water can’t be stopped — like in Avant’s neighborhood — the city is focused on minimizing damage. In these areas, city officials want to help elevate homes, fill basements with sand and move electrical or mechanical equipment. A new zoning code encourages building on higher ground. Developers can earn points, required of all new developments, by buying at-risk properties and allowing Norfolk to use them for flood control.

“Some areas of the city will be much smaller than now,” said Matthew Simons, Norfolk’s deputy resilience officer, as we walked around the historically Black neighborhood of Chesterfield Heights. There, flood-prone homes are now protected by tidal gates, massive pumps, nature trails, restored wetlands and a massive earthen berm.

Is Norfolk a model for the rest of the country? Perhaps.

AlphaGeo says rising threats from hurricanes, coastal and inland flooding, and heat rise put the city at high risk. But it ranks Norfolk’s resilience equally high: the city’s energy grid, health care, infrastructure and economic growth receive good marks, trailed only by social indicators such as income inequality.

But U.S. taxpayers are underwriting much of Norfolk’s most ambitious infrastructure. The region is home to 18 military bases, shipyards and military facilities, including Naval Station Norfolk, the world’s largest naval base. “Norfolk is the security center of the world,” said Kyle Spencer, the city’s chief resilience officer. “That’s why we have to make this work.”

It’s not yet clear how Norfolk will cover its share of the Army Corps’ original plan focused on major Atlantic storms: 35 percent will have to come from the city, state or elsewhere. Major changes to address flooding from rising sea levels or extend the proposed seawall to neighborhoods like Avant’s may not be covered by federal funding. The Corps faces a $109 billion project backlog, and plenty of bigger U.S. cities — including Miami and Boston — are demanding more comprehensive defenses.

Whatever happens, Simons said, some Norfolk residents “should expect to live with the water.”

One of them is David Moody, 59. He recently bought his dream home on Willoughby Spit, a narrow strip of sand squeezed between the Atlantic Ocean and the James River.

A mechanical engineer by training, Moody has spent countless weekends working to ensure that when the water arrives, his 1925 house stays dry — digging drainage trenches around his foundation, installing a pump, raising his front yard and burying drums to store water.

Hiring contractors, he estimates, would have tripled the $100,000 cost. “It’s tough for the average person to do what’s necessary,” Moody said.

Put the Pacific Ocean at your back, drive along the blue ribbon of California’s American River, and you’ll arrive in the foothills of Placer County. It is surrounded by dense stands of ponderosa pine, cedar and juniper that rise up the flanks of the Sierra Nevada range. Each year, millions of people drive through to Lake Tahoe’s ski resorts.

For many people living here, those winding roads and vast forests now look like a death trap.

The reality hit home on Nov. 8, 2018, after a power line sparked a fire in the region’s tinder-dry forests. As the Camp Fire engulfed town after town, there was little time to flee.

Nowhere suffered more than Paradise, a town of 27,000 about 100 miles north of Placer County. Almost every structure was razed by the flames. The city’s one route to escape, normally a 20-minute drive, became a four-hour morass.

It became the deadliest wildfire in California history, with 85 people dead. At least seven of the victims were trapped in their cars trying to escape. Paradise never recovered. The city now has about 8,300 residents, less than half its earlier population. Local homeowner insurance rates have hit $12,000 per year.

As climate change primes more of California to burnthan ever before, Paradise stands as a cautionary tale. “The Camp Fire changed everybody’s attitude,” said Kerri Timmer, the regional forest health coordinator for Placer County. “If it can happen there, it can happen here.”

Timmer is charged with ensuring it doesn’t.

When we looked for a place in the United States at extreme risk of fire and drought, Placer County rose near the top. But it also ranked among the most resilient.

Despite having more dead trees and homes near the forest edge than almost any other county in California, Placer also has the most communities enrolled in Firewise, a voluntary national program to harden homes against wildfire. The local government is spending tens of millions of dollars on forestry management and resilience efforts to prevent the next big burn.

If done right, communities can be saved even as wildfires rage around them, said Michele Steinberg, who directs wildfire outreach at the nonprofit National Fire Protection Association. Homeowners in Christmas Valley, a nearby Firewise site, spent a decade replacing wood roofs, and clearing dead and dying trees. It allowed firefighters to defend the community from the 2021 Caldor Fire near Lake Tahoe, without losing a single home.

But in Placer, Timmer said the county also had to “move faster and do more”: Programs that once could take five years are now being done in 18 months, and they’re no longer waiting for grants, but starting new programs even as they apply for more funding.

Beyond looking up your city’s score, how can you tell you’re living in a resilient community?

First, says Timmer, see if your local government cares enough to hire someone to take on risks and talk to residents. It doesn’t have to be a chief resilience officer. “Is there someone to call?” Timmer offered. “Does the county care enough that they have staff whose job is just this? You know, that’s me.”

Then look hard at the decisions made by city leaders. Avoid places making bad investments that don’t offer long-term protection, often called resilience traps.

After Hurricane Katrina, most homes in New Orleans were rebuilt in the same flood-prone places without accounting for the growing costs of pumps and levees to defend them. “I don’t consider that an act of resilience,” said Stone at the Georgia Institute of Technology, who advocates “retreat by design,” allowing cities to reinvest in more defensible areas.

Instead, pick places investing in the future by making hard choices today. Take Virginia Beach. In 2018, the city blocked developers from building on 50 swampy acres arguing the homes were vulnerable to sea-level rise and promised massive infrastructure expenses for the city. Voters doubled down by raising their annual property taxes by about $150 for the typical home and issued a $568 million bond to combat rising seas. It passed with more than 70 percent support.

And hard infrastructure isn’t everything. Resilience is much closer to home as well. The strength of a community’s social ties predicts how well it will fare in a crisis, said Michael Berkowitz, executive director of the University of Miami’s Climate Resilience Academy, citing events ranging from the covid pandemic to a 1995 heat wave in Chicago that killed at least 500 people, mostly seniors. Despite Chicago enduring temperatures above 100 degrees for days, death rates were far worse in neighborhoods where few neighbors knew each other, commercial life was hollowed out and populations had collapsed amid deindustrialization.

“Give me a disaster,” he said, “and I’ll show you how social cohesion will lead to a more resilient outcome.”

Finally, no silver bullet exists to weather climate change. Resilience looks different in every city because the risks are different.

While AlphaGeo’s customers use millions of data points to find the most resilient properties, Khanna said, the typical homeowner can boil it down to just a few factors: a strong economy; population growth; private reinvestment in the community; stable insurance rates; and smart public investments to combat a city’s top risk factors.

Finding a low-risk, high-resilience city is ideal, but “you could do much, much worse than just having that handy dandy checklist of a few things,” he said, even if you can’t get all of them. “It’s what we did to figure out where my parents would live.”

They chose a retirement community near Sacramento.

It’s not risk free: Drought and wildlife pose a danger. But Khanna argued they were lucky. Sacramento offered affordability along with good health care and infrastructure, the kind of resilient community the United States will need more of in the future.