WILSON, N.C. — City planner John Morck had an ambitious plan to fix a chronic flood problem — and a racial injustice.

Decades ago, officials in this former tobacco-farming town built public housing next to a creek that overflowed, causing the barracks-style apartments to flood repeatedly. The city of Wilson condemned 52 buildings in 2017, leaving them as boarded-up blights in a low-income, predominantly Black neighborhood.

But when Wilson asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency last year for $12 million to demolish the homes and rebuild on higher ground, the agency said no.

The decision points to biases within FEMA’s flood grant programs, which for years have favored wealthy or white areas.

“Sometimes the resources don’t go where they’re supposed to,” Morck said. “They’re supposed to give money where the need is.”

FEMA has allocated billions of dollars of flood-mitigation money using a racially inequitable system that has favored saving flood-prone houses in rich areas or in communities that are almost entirely white, using costly projects that elevate the homes above flood levels, an investigation by POLITICO’s E&E News shows.

The elevation grants have helped turn dozens of wealthy or overwhelmingly white areas into enclaves of climate resilience. The communities are seeing rising property values and economic stability, while much of the nation faces devastating effects of rising seas and intensifying floods.

“Sometimes the resources don’t go where they’re supposed to. They’re supposed to give money where the need is.”

John Morck, city planner, Wilson, N.C.

Some of the country’s richest communities, from the Connecticut Gold Coast to the Florida Treasure Coast, have received millions of dollars to elevate waterfront houses. Those homeowners have profited from huge reductions in insurance costs and in some cases have sold newly elevated homes for hundreds of thousands of dollars more than their purchase price.

“There’s a terrible equity issue here,” said Philip Bedient, a flood expert and engineering professor at Rice University in Houston. In the Houston area, “a lot of houses have been lifted, but predominantly they have been lifted in the more affluent neighborhoods.”

Policies set by Congress, FEMA and state officials over three decades have made it nearly impossible for people who are Black or Hispanic, or who have limited income, to get federal elevation money in most states, E&E News found.

Because the money is restricted to people who own homes and who in most cases can pay tens of thousands of dollars for costs not covered by FEMA, Black and Hispanic people are penalized due to the nation’s huge racial and ethnic disparities in wealth and home ownership.

Federal lawmakers of both parties and FEMA have known for years about biases in the allocation of elevation funds but did nothing until August, when FEMA — in a tacit acknowledgment of the unfairness — took a small step to help disadvantaged communities win flood grants. The agency does not track the race or income of grant recipients.

FEMA is facing unprecedented scrutiny over equity in both its grant programs and the emergency aid it gives communities and individuals after disasters. The agency’s administrator, Deanne Criswell, said last year she ordered an “equity-based review of all of FEMA’s grant programs.”

E&E News analyzed FEMA databases containing tens of thousands of grant records, reviewed thousands of pages of state and local documents and property records, conducted more than two dozen interviews, and visited a half-dozen communities that have faced major flooding.

The analysis shows clear race- and wealth-based impacts in most of the 18 states that have received nearly all of the FEMA elevation funds.

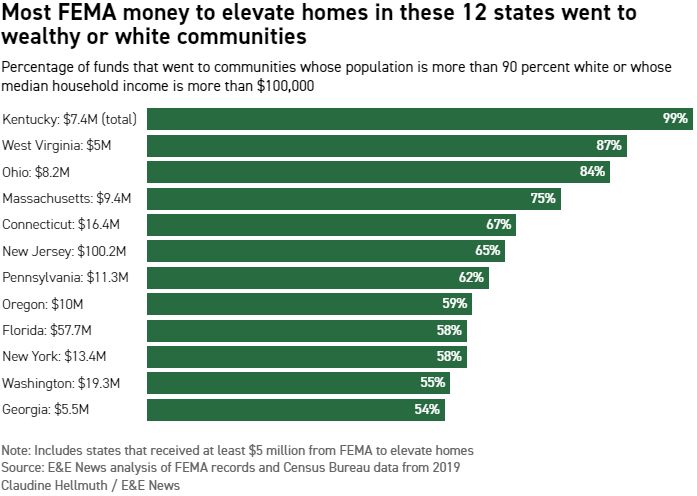

In 12 of the 18 states, more than half of the FEMA elevation money has gone to communities that are wealthy or almost entirely white. In four states — Kentucky, Massachusetts, Ohio and West Virginia — more than 75 percent of the FEMA elevation money has gone to wealthy or overwhelmingly white communities. And in six states, at least 40 percent of the elevation money has gone to a single affluent or almost entirely white community.

“These programs have severe consequences for people of color, who have historically been marginalized. They’re too poor to qualify for help,” said Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), who has worked to reform FEMA grant programs.

FEMA Acting Associate Administrator for Resilience David Maurstad accepted E&E’s findings.

“I don’t disagree with the point that you’re making,” he said in an interview.

FEMA declined to explain its rejection of Wilson’s application beyond saying it “was prioritized below more competitive projects.” But the agency acknowledges that its flood programs are stained with equity problems.

“Do we need to see different outcomes? I think the answer is yes,” Maurstad said. “That’s why we’re looking at the programs to determine what we can do to reduce the barriers for homeowners in disadvantaged areas.”

Federal elevation grants can change the trajectory of a family’s fortune.

Worth as much as $550,000, they are the triple crown of flood mitigation. Elevation projects increase the value of a home, protect it from flooding and destruction, and save recipients tens of thousands of dollars in insurance costs.

Some homeowners profit directly from the grants by selling elevated homes.

In Old Greenwich, Conn., one of the nation’s richest communities, a couple received $100,000 from FEMA in 2018 to help elevate the luxurious waterfront home they had bought 16 years earlier for $1.33 million.

The Colonial-style house, which was flooded during Superstorm Sandy in 2012, features four bedrooms, four bathrooms, two fireplaces, a swimming pool and faces Greenwich Cove near the Long Island Sound.

Two-and-a-half years after the elevation was finished, the couple sold the home for $3.17 million, town records show.

Price increase: $1.84 million.

There are hundreds of examples of people selling homes within a few years of getting FEMA money for elevation projects. Nothing prohibits homeowners from selling their house immediately after FEMA pays to improve it. And many factors in addition to an elevation project can increase a property’s value.

In Ormond Beach, Fla., a city on the Atlantic coast that’s 85 percent white, five of 10 homeowners who received FEMA grants sold their homes after they were elevated. One couple got $310,000 from FEMA in 2012 to elevate a five-bedroom house they had bought a year earlier for $200,000.

After the elevation, the couple sold the home for $520,000.

In Connecticut, E&E News obtained addresses of 62 homes that FEMA has paid millions to elevate in Old Greenwich and the affluent neighboring towns of Fairfield and Westport since the mid-2010s. Eleven have been sold.

Average sale price: $1.7 million.

“It was a bonanza,” said David Harmuth, a real estate agent in Old Greenwich. “For the homeowner, it was free money to lift their house.”

Another Old Greenwich couple sold their five-bedroom home in 2018 for $3.1 million just 66 days after the FEMA-funded elevation was complete, town records show. Old Greenwich is a community in the town of Greenwich.

FEMA discovered in 2020 that the owners had used elevation funds improperly to build a 1,300-square-foot addition and forced the state to repay the $90,000 grant, according to court documents. The town of Greenwich is suing the former homeowner for the money.

Nanci and Jonathan Lewis received $100,000 from FEMA to elevate their 3,900-square-foot home in 2018 across the street from the beach in Fairfield. The home had been flooded during Superstorm Sandy, and the Lewises spent at least $150,000 of their own money on the elevation, which lifted the house about 5 feet.

The FEMA-funded project added a room to the house and led to a drastic cut in the Lewises’ insurance rates while also improving their view of the Long Island Sound across the street.

“We definitely had more water view,” Nanci Lewis said in an interview.

In 2020, after the elevation was finished, the town of Fairfield doubled the home’s value to $2 million, town records show. The Lewises sold the house for $2.1 million the following year.

“I don’t necessarily agree that it’s just given to people in nice communities so they can sell their home and make more money,” Nanci Lewis said of the FEMA grants. “It helps everybody … by keeping the community and the [property] values that everyone benefits from.”

In a handful of states, FEMA elevation money has been distributed more equitably. That’s happened mostly when homeowners didn’t have to pay a portion of the project due to additional funding from states or FEMA.

North Carolina and Virginia have policies requiring their state governments to pay the share of many mitigation projects that FEMA does not cover. FEMA typically pays 75 percent of project costs.

By paying the remaining 25 percent, North Carolina and Virginia have enabled thousands of low-income homeowners to get FEMA elevation funds.

“The state paying that 25 percent nonfederal share is really helping the people that need it the most,” said Michael Sprayberry, who ran North Carolina emergency operations from 2013 to 2021.

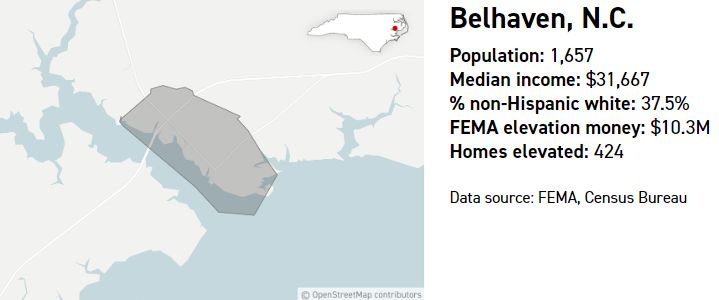

In North Carolina, the top recipient of FEMA elevation funding is Belhaven, a low-income former fishing village near the coast whose population of 1,700 people is roughly 50 percent Black. Belhaven has received $10 million to raise more than 400 homes, mostly after Hurricane Fran, in 1996, swamped the town.

In Virginia, the top recipients of elevation money are Norfolk and Hampton – two large cities where white people are a minority.

Louisiana also has seen extensive elevation work in low-income minority areas in and around New Orleans. The projects were done mostly after Hurricane Katrina, when FEMA and other agencies poured tens of billions of dollars into an unparalleled rebuilding effort.

Louisiana has received more elevation funding than every other state combined – roughly $1.3 billion. For most elevation projects, FEMA paid the full cost, agency records show.

Elevation is a monthslong process. A contractor burrows under a house with jacks to lift the structure and installs new foundation walls that raise the home as much as 15 feet above the ground. Beachfront homes are typically rebuilt on wood pilings, or “stilts,” that let tidal surges flow underneath. Some projects involve completely rebuilding a house at higher elevation.

FEMA itself boasts that an elevation project “increases the value of your property” and reduces flood insurance costs.

The agency runs the nation’s largest flood insurance program, covering 5 million properties. FEMA slashes premiums both for homeowners who protect their houses from flood damage and for entire communities with a large number of elevated houses. That means recipients of FEMA grants benefit financially for years by paying lower flood insurance rates.

On the Alabama coast, FEMA has paid to elevate 40 homes in Baldwin County, which is 83 percent white.

“Countywide, our residents are saving around $1 million a year” in flood insurance premiums, said Eddie Harper, the county’s coastal area program director.

“I invested $50,000 and got $500,000 back. On my side, that’s the real deal. But on the taxpayer’s side, it’s like WTF?”

Iris Eisenberg, grant recipient

In Florida, Iris Eisenberg was facing annual premiums of nearly $20,000 after her Jacksonville home flooded several times in the late 2000s. She collected roughly $75,000 in claims payments.

Then Eisenberg, a pediatrician, got $453,304 from FEMA to elevate her four-bedroom, Mediterranean-style house in a historic district along the St. Johns River. Eisenberg paid 10 percent of the project cost, or $50,367.

When the elevation was finished in 2014, Eisenberg’s insurance premium dropped to $800 a year.

“I invested $50,000 and got $500,000 back,” Eisenberg said, estimating her long-term savings on insurance. “On my side, that’s the real deal. But on the taxpayer’s side, it’s like WTF?”

FEMA has spent $2 billion to elevate 14,400 flood-prone homes since the early 1990s, the agency says.

Created four decades ago amid rising disasters costs, the programs have grown in stature and ambition. Congress and the Biden administration poured billions of additional dollars into the programs in the past year, giving them a central role in the federal strategy for climate change.

The grant programs are highly competitive. As FEMA and states allocate more money for elevating homes, less money is available for projects that protect entire communities, such as installing large pumps and tunnels for flood protection and rehabilitating wetlands. Studies show those are more effective at preventing damage.

“Elevation is really not that cost-effective,” said Carolyn Kousky, executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Risk Center and a leading expert on flood risk. “If your only metric is lowering flood damages, you’re wasting dollars.”

But in some affluent areas, the grants have become a key to climate adaptation. Officials and homeowners increasingly look to elevation projects to preserve homes and communities threatened by rising seas and intensifying floods.

Elevation projects are now more popular than FEMA’s well-known buyout program, which pays homeowners for their flood-prone properties, demolishes the houses and leaves the land vacant.

Buyouts have been used largely by states, counties and big cities, which have used FEMA money to clear large swaths of flood-prone land, sometimes demolishing entire communities.

Elevation grants by contrast have been popular with small, affluent and overwhelmingly white towns trying to protect high-priced property.

In Kentucky, where FEMA has spent $7.4 million on elevations, 90 percent of the money has gone to one community: Prospect, a riverfront city of 4,900 people near Louisville. Its income level is nearly triple the state average.

In Washington state, 42 percent of FEMA elevation funds have been spent in Snoqualmie, a city of 13,500 people east of Seattle where the median household income is $145,600.

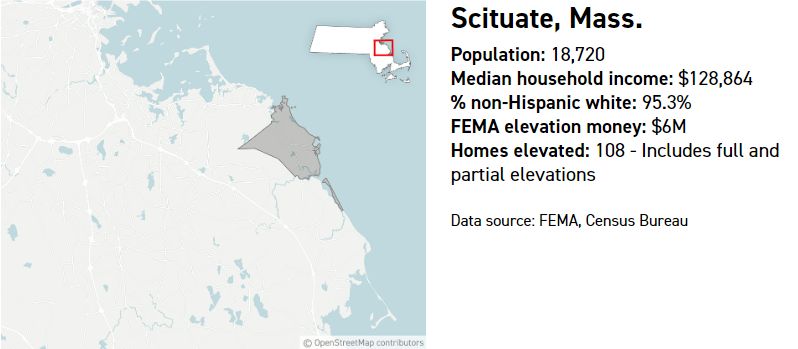

In Massachusetts, nearly two-thirds of the $9.4 million in FEMA elevation funds have been spent in Scituate, a coastal town of 19,000 people outside Boston and one of the state’s richest municipalities. Its population is 95 percent white.

These communities have a crucial edge in winning elevation grants: the money to hire a consultant or employee to write the applications.

“Scituate has invested in a full-time coastal resilience staff person. That person is able to devote time and effort and expertise to writing the grants,” said Sarah Murdock, a former member of the Scituate Coastal Advisory Commission and head of climate resilience at the Nature Conservancy. “Those are factors that make it impossible for lower-income communities to compete against a town like Scituate.”

FEMA itself recognizes the unfairness of an application process that costs tens of thousands of dollars and is open only to communities that have a formal hazard mitigation plan.

“In some richer jurisdictions, more affluent jurisdictions, where you have more people, you can pay a consultant to do grants for you,” Victoria Salinas, a FEMA associate administrator, said at a FEMA Civil Rights Summit in November.

Salinas has been working on the equity assessments ordered by Criswell, the agency’s administrator, and they have been eye-opening.

“The list of how systemic racism and inequity shows up is really long,” Salinas said.

Florida is one of the best illustrations of inequity in elevation grants.

It’s not surprising that FEMA has spent $58 million over the past 25 years to elevate roughly 400 homes in one of the nation’s most flood-prone states.

The oddity is where the money has gone.

Flood damage has occurred virtually everywhere in Florida. Nearly 100 cities have sustained more than $10 million in flood damage since the late 1970s, FEMA insurance records show.

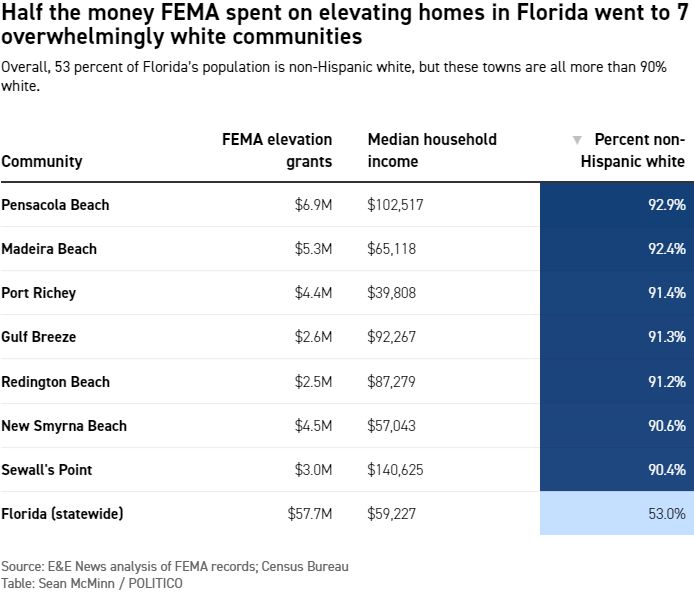

But half of FEMA’s elevation money has gone to seven towns dotting the Atlantic or Gulf coasts.

The towns are tiny. With an average population of 7,600, they account for 0.2 percent of the state’s population and 10 percent of Florida’s federally insured flood damage.

And they share one other trait: They are demographic anomalies.

In a state where 53 percent of the population is white, each town is more than 90 percent white.

“Those tiny little communities have very expensive properties, and they have the resources to get those [elevation] funds,” said former FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate, who ran the Florida Division of Emergency Management in the 2000s.

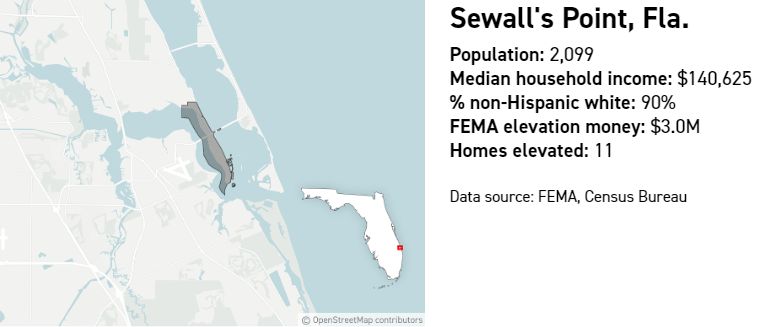

One Atlantic coast town, an enclave of 2,000 people called Sewall’s Point, got $3 million to elevate 11 homes in the early 2010s. For 10 of the homes, FEMA covered the full cost of the elevations under a special program that directed the agency to pay the entirety of flood-mitigation projects in communities with limited resources.

Sewall’s Point is one of the richest places in Florida, with a median household income of $141,000.

Kelly Winslow, for example, got $317,210 from FEMA to elevate his five-bedroom, 3,800-square-foot house in 2013.

The two-story house sits on an acre of land and resembles a resort, with towering palm trees, a small private beach on a coastal waterway, a swimming pool, a second-floor balcony, a 2,000-square-foot patio, an outdoor bar and a gangway jutting 100 feet into the water.

After back-to-back hurricanes in 2004 submerged the house in 2 feet of water, the town condemned the home, Winslow said. He and his wife, Audrey, spent tens of thousands of dollars on cleanup and repairs.

After the elevation, “that house will never flood again,” Winslow said. “It’s bulletproof.”

The elevation also helped the Winslows sell the house — for $1.1 million more than they paid for it. Their purchase price in 2004 was $950,000. The sale price in 2016 was $2.05 million.

“If you didn’t lift it you were going to have a hard time selling the house, especially for a house that had been flooded twice before,” said Winslow, who now lives in the mountains in North Carolina.

“It was a great opportunity but it was by no means taking advantage of money to make profit,” Winslow added. “It was taking advantage of a grant to make something habitable.”

In August, FEMA announced a small but significant step toward improving equity in one of its two programs that fund flood projects.

The Flood Mitigation Assistance Program, which distributes roughly $200 million in grants annually, will start this year giving priority to projects in areas with high rates of poverty, unemployment and other indicators of “social vulnerability” to disasters.

The way that we’ve been delivering our programs … has had an unintended consequence of creating inequities, it certainly wasn’t intentional.

Deanne Criswell, FEMA administrator

Criswell, the FEMA administrator, has said one of her priorities is making the money more accessible to marginalized people and communities that have faced barriers when seeking funds. The barriers, Criswell said, are an inadvertent result of program design.

“The way that we’ve been delivering our programs … has had an unintended consequence of creating inequities,” Criswell said during a session with journalists in February. “It certainly wasn’t intentional.”

When Congress created programs for elevating homes, its goal was not to protect flood-prone communities or to help towns that couldn’t afford flood protection.

Congress’ goal was to protect taxpayers.

The elevation programs began after the Great Flood of 1993 demolished communities across the Midwest and the northern Plains. The Mississippi and Missouri rivers overran or destroyed more than 1,000 levees, causing $41 billion in damage and forcing officials to reconsider the century-old strategy of trying to contain waterways behind walls, dikes and other structures.

The new strategy involved moving homes out of flood zones through demolition or elevation.

The main threat to taxpayers came from FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, which covers 5 million properties and relies on both premiums and taxpayers to pay claims. NFIP policyholders can collect up to $250,000 per claim — far more than the few thousand dollars an uninsured homeowner typically gets in FEMA disaster aid. That exposed taxpayers to billions of dollars in financial losses.

Facing huge financial risks, Congress prioritized those 5 million insured properties when it created grant programs to reduce flood damage.

Congress also required a grant recipient to own the home that was being mitigated.

And those homeowners usually had to pay 25 percent of the project cost, which amounts to as much as $75,000.

But those prerequisites had a devastating effect: Each one effectively discriminates against Black, Hispanic and low-income households because they are among the least likely to own a home, have FEMA flood insurance and be able to afford their share of an elevation project.

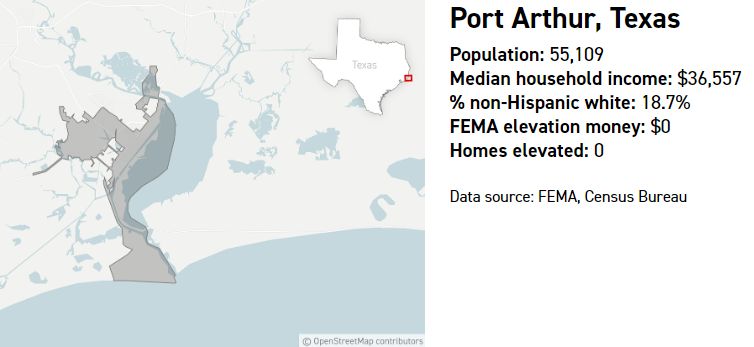

“It is racial discrimination when someone has to come up with $50,000 to get $200,000 to elevate your home,” said Hilton Kelley, an environmental justice advocate in Port Arthur, Texas. “Many people in this community could not possibly meet that.”

Port Arthur, a coastal city where Black and Hispanic people comprise a majority of residents, has sustained more flood damage than all but 14 cities in the U.S. It has not received any FEMA money to elevate homes.

Federal statistics show the discriminatory effect of Congress’ criteria.

Median wealth is $24,100 for Black households, $36,100 for Hispanic households — and $184,000 for white households.

Home ownership also is skewed: 74 percent of white households own the home they occupy compared to 45 percent of Black households and 49 percent of Hispanic households, according to Census Bureau data.

FEMA’s own reports show that people with federal flood insurance have nearly twice the income as people without it. In flood-prone states such as Louisiana and Texas, the disparity is even greater.

“Very few low-income people buy flood insurance,” said Leonard Shabman, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future who chaired a congressionally mandated committee that studied the affordability of flood insurance.

“In many parts of the country, low-income people are not property owners, they are renters. So right away you begin to see where this is going,” Shabman added.

More than 97 percent of all elevated residences are single-family homes, FEMA records show.

In 2004, FEMA hired the University of North Carolina’s Center for Urban and Regional Studies to analyze the factors that encouraged and deterred homeowners from taking federal money to elevate their house or sell it to the government for demolition.

The biggest factor was money. Higher-income households were more likely to elevate or sell a flood-prone home because they have “economic resources to provide a match,” the report found.

“The report was a warning to FEMA and Congress,” study author James Fraser said in an interview.

One of the most unusual FEMA elevation projects reveals how the federal government is focused on reducing insurance claims — rather than protecting communities from flooding.

In 2020, FEMA gave Ricky and JoAnn Sims $386,000 to elevate their home in Teague, Texas, by 12 feet.

The Simses live nowhere near the coast or a major river. They live 150 miles north of Houston in a rural county whose flood risk FEMA rates as “relatively low.”

“We’re kind of landlocked and there’s just not a lot of flooding that goes on in Teague,” Ricky Sims said.

The only nearby water is a channel that overflowed into the Simses’ home in October 2013 and again in June 2016. It ruined carpet, furniture and drywall. The Simses collected $322,132 from FEMA’s flood insurance program, FEMA records show.

And that was enough to show that it made financial sense to elevate the Simses’ home.

The agency uses a cost-benefit analysis to select elevation projects based on how much money a project could avert in future flood insurance claims.

“We have to prioritize eliminating or reducing the risk of flood damage to residences that are insured through the NFIP,” said Maurstad, the FEMA acting associate administrator. He noted that FEMA flood insurance premiums pay for some elevation projects.

In some cases, grants are used to raise second homes near the beach.

Those are communities where flooding primarily damages rental homes, many of which are occupied only in the summer.

“Nobody at FEMA circles predominantly white enclaves of rich people and says that’s where we want to mitigate,” said Fugate, the former FEMA administrator. “But your bias is toward projects that give you the greatest savings. That tends to favor affluent areas because those higher-value properties give you the best return on that investment.”

To be eligible for FEMA funding, an elevation project must be “cost effective,” according to agency guidance. In federal lexicon, “cost effective” means the amount spent to elevate a home must not exceed the estimated flood damage that would occur if the house wasn’t raised.

The cost-effectiveness requirement gives an advantage to expensive properties in affluent areas, said Vanessa Castillo, deputy director of mitigation at Hagerty Consulting, which advises governments on disaster response.

Those homes generally have higher quality construction and are in regions where labor and materials are more expensive. When a local official estimates the savings from elevating a home, it will be higher for well-built homes in expensive areas because they cost more to repair after a flood, Castillo said.

“The cost to rebuild a 2,000-square-foot home in the [San Francisco] Bay Area is going to be much higher than the cost to build that same home in rural Iowa. That’s where you get this skew,” Castillo said. “You get more benefits if you’re in an expensive part of the country.”

As elevation projects have become increasingly expensive and clustered in affluent areas, that has made them more controversial.

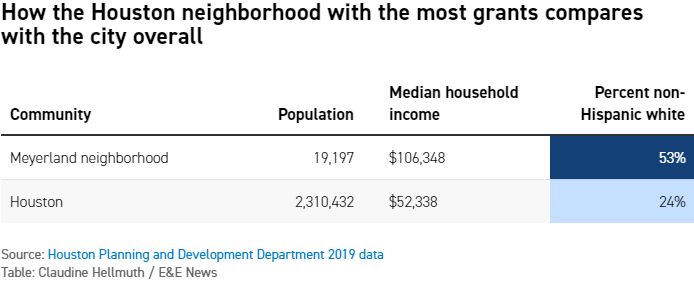

One of the biggest recipients of FEMA elevation dollars is Houston, where less than a quarter of the 2.3 million residents are white. But the spending is not as equitable as it may seem.

E&E News obtained records for the 49 Houston homes whose owners have signed elevation contracts and found that 30 of the houses are in one of the city’s richest neighborhoods. The income level in Meyerland is more than double the city average.

FEMA is spending an average of $336,353 on the elevation projects in Meyerland, according to an E&E News analysis. Fourteen of the homes have backyard pools, city records show.

Several Houston City Council members have voted against the elevation projects, calling the spending excessive.

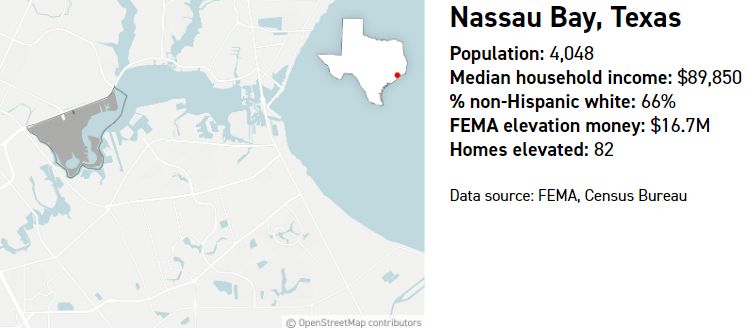

Next to Houston, the small city of Nassau Bay has been an epicenter of elevations. It’s received nearly $17 million from FEMA since 2013.

Nassau Bay is wealthy and white compared to surrounding Harris County. The city does not meet E&E News’ definition of overwhelmingly white or wealthy. But its affluence has played a vital role in receiving elevation funding, said Jason Reynolds, the city manager from 2015 through 2021.

“You have to find homeowners who are willing to do this and have the capital to move forward,” Reynolds said in an interview. “It’s difficult for a city that does not have the ability for homeowners to pay this amount of money.”

Nassau Bay homeowners said they spent as much as $125,000 each on their elevations. That money paid mostly for the portion of a project’s cost that was not covered by FEMA. Homeowners also had to pay for aesthetic upgrades such as installing siding to cover a new cinder block foundation under a city ordinance that required elevated homes to blend into the neighborhood.

Donald Matter, Nassau Bay’s mayor pro tem and one of the first homeowners in the city to have his home elevated, said “one or two people balked at” the aesthetics requirement.

“If you can’t put $10,000 into a house after FEMA’s improved it by spending $200,000, I don’t have much sympathy,” said Matter, who estimated he spent up to $125,000 on his own elevation project. “They shouldn’t be here to begin with.”

FEMA grants sometimes lead to political battles between communities within a state.

When FEMA gave Connecticut $12 million after Superstorm Sandy for flooding and other mitigation projects, state officials initially planned to spend the money on improving infrastructure.

Communitywide projects “would provide the greatest benefit to the most number of people,” state officials wrote in an internal memo.

In Bridgeport — the state’s largest city and one of its most impoverished — officials asked FEMA for $4 million to rebuild a seawall along the Long Island Sound. The project would protect a neighborhood occupied almost exclusively by Black and Hispanic people, many of whom lived in a large public housing complex.

But state officials changed their priorities when affluent communities such as Greenwich complained that they needed the FEMA money to elevate flood-damaged homes.

“There was a big outcry because it was like, how do we help our residents?” recalled Denise Savageau, who was Greenwich’s city conservation director.

The state allocated $3.6 million of the FEMA money for elevation projects, most of which were in Greenwich, Westport and Fairfield — three of the state’s richest communities. The 22 houses that were elevated have an average value of $1.5 million.

Savageau said state officials made the change after they learned Congress had approved several billion dollars for Sandy recovery, which offered additional funding opportunities for the Bridgeport project.

Savageau said that “$1 million is not an expensive home in Greenwich. That’s an entry-level home in Greenwich. We have homes on the shoreline that are selling for $30 [million] to $40 million.”

The state used the remaining FEMA money to pay for some property acquisitions and infrastructure projects, but not in Bridgeport. The city eventually got federal reconstruction money through the Department of Housing and Urban Development to rebuild flood-damaged public housing.

Denese Taylor-Moye, a former Bridgeport city councilwoman who represented the flooded area, wasn’t surprised that FEMA money went to save homes in rich communities instead of to protect low-income residents.

“It’s much harder for us to get things that people who live in prime areas get,” Taylor-Moye said. “Whether people want to admit it or not, they’d rather give that type of money to affluent places to make sure they stay affluent.”