As an upsurge in coronavirus infections stretches thin the capacity of health care workers and emergency managers nationwide, the Midwest is bracing for another battle: a potentially devastating flood season.

“The current situation with COVID-19 presents us a fight on two fronts: one front, we have the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, and on the other, what promises to be a very active spring 2020 flood season,” Sharon Broome, mayor of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, said on a press call Thursday.

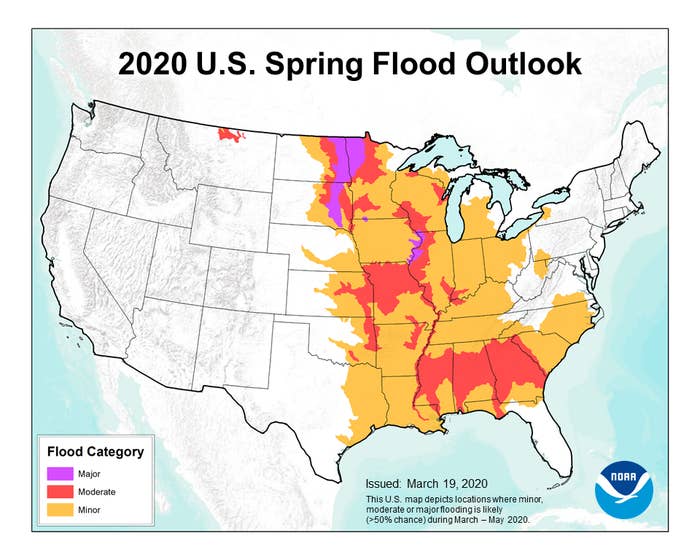

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration this week released its spring flood projections, predicting moderate to severe flooding in 23 states. The greatest risk for “major and moderate flood conditions,” federal experts say, is along parts of the Mississippi River basin.

For local leaders in the Midwest, this situation is offering a crash course in how to plan and respond to multiple types of disasters simultaneously. And in a warming world, overlapping and compounding disasters will likely be the new normal. Human-caused climate change is already increasing the intensity and likelihood of certain extreme weather events, including heavy rain and related flooding in the middle of the country.

“We’re good at responding when a disaster stares us in the face,” Kris Johnson, deputy director at the Nature Conservancy, told BuzzFeed News. “But we’re really not good at thinking about what can we do now to mitigate and dampen the potential impacts and increase our ability to be resilient to future impacts, whether they are public health–related or whether they are flooding.”

According to Broome, a network of regional mayors has been preparing for possible flooding for weeks, coordinating with each other, the Red Cross, Congress, and federal agencies like the Federal Emergency Management Agency. But the pandemic is complicating matters, requiring more virtual coordination and forcing planners to update response and recovery protocols to take into account the specific threats of the pandemic.

“I think we can anticipate that as we move forward, we will see more burnout for our first responders, greater depletions of our supplies, and greater demand for more recovery money,” said Alice Hill, a climate fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who has also studied pandemics.

So far, local officials have been tallying and growing reserves of personal protective equipment (PPE) for first responders, volunteers, and others involved in the anticipated flood response, including head coverings, masks, gloves, and goggles. In some areas, the distribution of premade sandbags to vulnerable communities has already started to avoid a last-minute rush if and when catastrophe strikes.

One area of disaster management that's especially complicated by the pandemic is sheltering displaced people. Red Cross members are planning to work with local officials to see if there are hotels or dorms available to give people displaced by flooding shelter while also keeping them separated enough to prevent the potential spread of the virus. If a shelter needs to be set up, people coming in would also get screened for symptoms of COVID-19, such as by getting their temperatures checked, according to Trevor Riggen, senior vice president of disaster cycle services at the American Red Cross. Anyone exhibiting symptoms would be isolated.

“We’d have additional screening both for our volunteers and clients in the shelter three times a day to make sure if someone was asymptomatic when they came in and they presented while they were in the shelter, we could pick that up very quickly,” Riggen said. The Red Cross is also planning to stagger shelter meal times to avoid long lines, space out cots, set up extra handwashing stations, and do more vigorous cleaning.

There’s a big range in how prepared Mississippi River communities are for juggling the disasters, according to their mayors. Even the ones that said they were currently prepared expressed uncertainty about the future.

“Right now, Red Wing is ready for disaster,” said Sean Dowse, mayor of the Minnesota town. “We have the PPE. We have the personnel in place. What will happen in 2 weeks, we have no idea — because what will be coming down the road to us could be a surprise, and we’re going to have to be flexible going forward.”

For regions battling especially fast-growing coronavirus outbreaks, such as New Orleans and Baton Rouge in Louisiana, flood preparation is taking a backseat as they deal with the current crisis.

“I feel like more than anything, we’re just trying to keep our people in some state of calm as we daily put out these bleak circumstances, these bleak numbers,” said Belinda Constant, mayor of Gretna, Louisiana. “We’re just praying every day that we don’t end up in a state of anarchy.”