In some ways, Drew Heyen thought he had grown numb to disasters. His family’s ranch-style home flooded nine times in 17 years, including two weeks before Hurricane Harvey and during the storm itself.

Heyen figured the house would keep on flooding, since it bordered a gully. So together with his wife and two kids, he tried to prepare as much as possible.

“We didn’t have carpet. The floors were concrete floors. Most of our things that we owned were up off the floor. We had free-standing metal shelves, that kind of thing,” Heyen said.

But he can’t prepare the same way for the new coronavirus, the largely invisible threat that Heyen is particularly vulnerable to. He’s almost 50 years old and diabetic, and in December, he got a respiratory infection that doctors believe caused his heart to fail.

“I don’t like my odds if I were to pick up this virus,” said Heyen, who wears a personal defibrillator vest day and night until he gets a new pacemaker.

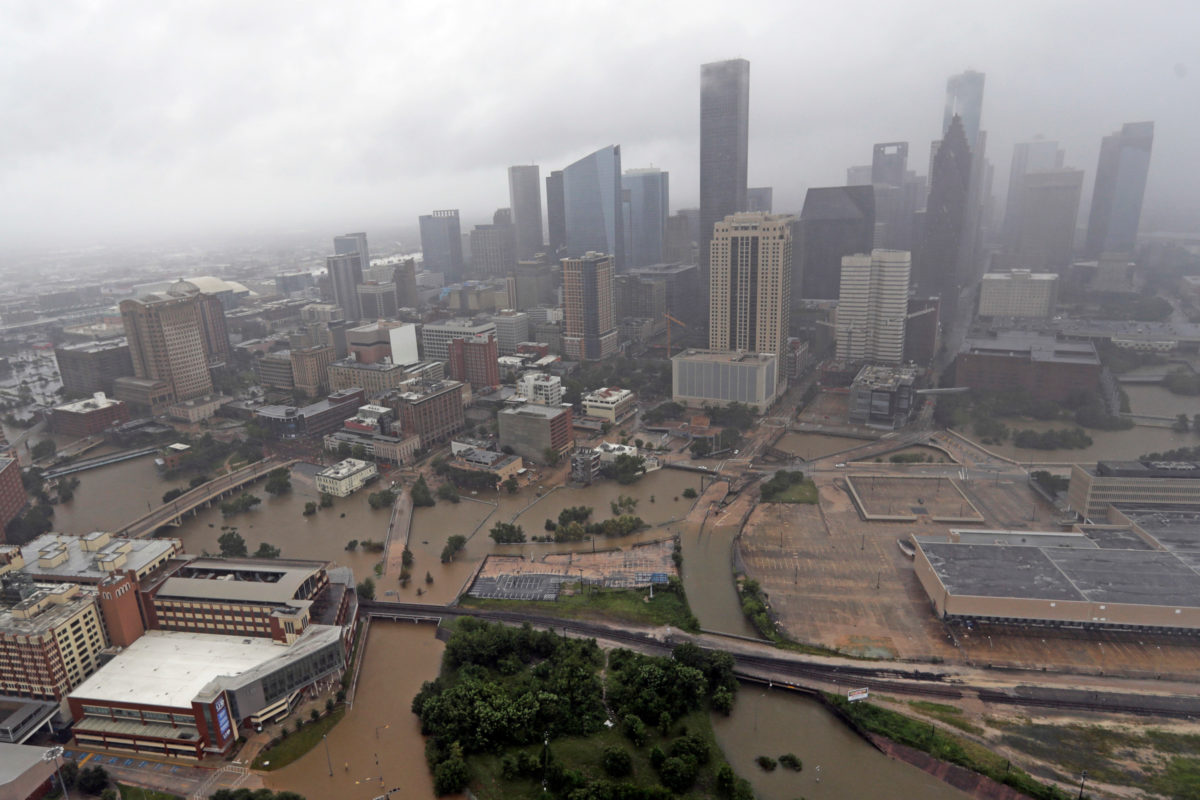

Houston’s built a reputation for being a resilient city. It endured the oil bust of the 1980s, the fraud and collapse of energy trading company Enron and multiple storms and floods that come year after year. But the novel coronavirus has unnerved even residents like Heyen, who’ve weathered so many other disasters.

The threat of the pandemic scares his wife so much, they don’t talk about it.

“Fear is my biggest complaint,” he said. “I’m literally terrified.”

As of Tuesday morning, more than 2,700 people in the greater Houston region have tested positive for the virus, including dozens of Houston firefighters and police officers, and at least 25 people have died. Among them: a beloved wife and mother in Pearland; three elderly men who lived at a luxury senior community in The Woodlands; and an elderly woman who lived in a Texas City nursing home with a history of violations.

But some worry many cases are going undetected because of the lack of widespread testing and a surge in hospital admissions.

“Really the most accurate information, because of the lack of widespread testing, comes from the hospitals,” Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo told Houston Public Media last week. “And so they’re still seeing their rates of COVID patients go up exponentially…So, we know right now we are very much tracking the path that Italy or New York were on.”

“It’s like a freight train”

In Kashmere Gardens, a historically black neighborhood in northeast Houston, Keith Downey has been trying to make sure 120 homebound seniors get meals. He’s still practicing social distancing because, as an asthmatic, he’s vulnerable to COVID-19. So he posts resources on social media and takes a lot of phone calls to help his community get through the pandemic.

“It’s like a freight train and you just can’t see the caboose, you know, because you don’t know how long this is going to last,” said Downey, president of the Kashmere Gardens super neighborhood.

During Harvey, the community got four-to-five feet of water. Downey said some residents are still dealing with mold and trying to rebuild. But now, he said, they’re also worried about getting sick from the virus — which some early data shows is disproportionately impacting African-American populations — and struggling to pay bills.

Many residents are suddenly out of work from their jobs at restaurants, offshore rigs, and other places — among the 600,000-plus Texans now unemployed.

“Rent is due, car notes are due, mortgages are due,” Downey said. “People are just saying, you know, ‘Where do I turn? Where is the stimulus check?’ You know, a lot of people are waiting on that. They can’t receive it fast enough.”

Houston’s long-term recovery could be tough because its economic engine — oil and gas — is getting hit from two sides. The virus has put the brakes on demand for things like gas and jet fuel, and a global price war is driving oil down to $20 dollars a barrel. Oilfield service giant Halliburton has already furloughed more than 3,000 workers in Houston and plans to lay off 350 employees in Oklahoma.

“This is territory both familiar and unfamiliar,” said Angela Blanchard, a disaster and recovery expert.

Virus vs. Hurricane

A Harvey flood evacuated child carries donated supplies in a trash bag at a shelter setup inside NRG Center, Wednesday, Aug. 30, 2017, in Houston. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

A Harvey flood evacuated child carries donated supplies in a trash bag at a shelter setup inside NRG Center, Wednesday, Aug. 30, 2017, in Houston. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

Blanchard, president emerita of the state’s largest community development organization, BakerRipley, and a senior fellow in disaster response at Brown University, said what’s so strange and painful with the virus is that the suffering isn’t out in the open like a hurricane. It’s private, almost hidden.

“The people struggling to breathe in hospitals are not visible,” she explained. “Right now, all the hundreds of thousands of people losing their jobs across the country, getting texts and emails that say don’t come in, that suffering and those fears are behind four walls where people are hunkered down.”

And in hurricanes, Houstonians are used to hunkering down and forecasting with familiar lingo about a wind event, or water event, or the “dirty side” of the storm.

But with the virus, Blanchard said it’s taken time for local leaders and residents to get up to speed on the “language and parameters of what this disaster means.”

“Like hurricanes, it’s a twin threat to our health and well-being and it’s a threat to our livelihoods,” Blanchard said. “We’re trying to form a shared understanding of what what we’re navigating.”

But she believes something else is very familiar: the willingness to help others when times get tough.

“The spirit of generosity is permanent,” Blanchard said. “It’s everywhere. And in Houston, we’ve witnessed it and practiced it so many times. We are, whether we realize it or not, on familiar ground.”