The threats to our cities seem endless - from flash flooding to pollution, overcrowding to the risk of pandemics.

To help avert crises, many cities have invested in technology - the theory being that if you can see the scale of the problem, you can start to work out what to do about it.

So sensors measuring crowds, river levels and pollution have gradually become as much a part of our urban infrastructure as lampposts and traffic lights.

But despite the investment, we have seen significant flash flooding across the globe this year, including in cities such as London and New York. So does the technology work?

A so-called smart flood prevention system was in place in the Chinese city of Zhengzhou when rainstorms caused at least 302 deaths in July.

The platform, from Aerospace Shenzhou Smart System Technology Company, promised to allow authorities to monitor water levels in real time through sensors and intelligent analysis. It had access to meteorological and hydrological data.

It is not clear if the system failed to spot the impending floods or whether the government simply failed to act on the information received but an investigation is continuing.

But on Chinese social media, some questioned whether such smart city tech was a waste of money.

UK company Previsico offers its own flood warning system and co-founder Dr Avi Baruch told the BBC that there may be lessons to learn, but that it "it would be wrong to rush to judgement".

He said such systems should work in tandem with other emergency planning.

"Businesses need to get up defences, protect key assets and arrive at the scene faster, if there is a warning," he said. "Local authorities need to consider bringing in pumps, clearing drains and closing off streets so that the issue of cars floating down streets can be eliminated."

Previsico is currently working with several cities, including London, Birmingham and Manchester, to forecast where flooding may happen.

Its live modelling system, which offers hyper-local forecasts to business customers and local authorities, was up and running when floods hit London in July, although the review of how well it worked has not yet been completed.

Robert Muggah is a political scientist and co-founder of the Igarape Institute, which looks at issues around urbanisation.

"There has been a lot of energy and investment going into smart technology to help cities mitigate and adapt to climate change but many haven't been thoroughly tested," he said. "We are seeing a lot of hype and also some very obvious limitations."

So, for instance, many cities have access to meteorological data that can accurately predict rainfall levels, but he says there are other factors to take into account.

"Cities have invested in laying down concrete and tarmac which is exacerbating the risk of flooding." He added: "It is not just about mapping precipitation and storm surges but also about understanding the built environment."

For cities where heat is an issue, the pressing need over the recent summer months was for technology that could help the fight against forest fires.

In California, firefighters have been using a programme known as FireGuard, which uses data from the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

This includes satellite data and imagery from military drones which is then aggregated, analysed and assessed by two teams of Air Force and Army National Guard intelligence analysts.

"From that they produce sanitised unclassified products that go out to the firefighting community," Major Jan Bender wrote on the US Department of Defense website.

The maps showing the location of fires are updated as often as every 15 minutes.

So when a fire trapped more than 100 hikers and campers in the Sierra National Forest in California, FireGuard gave an exact location allowing for a fast evacuation, which, according to firefighting chiefs, saved lives.

As cities start to build climate-related thinking into their everyday planning, they need to consider where they invest into technology and what their priorities are when it comes to potential disasters, says Mr Muggah.

Often the most exposed areas of a city are the ones least likely to have smart tech or, in some cases, even to be mapped.

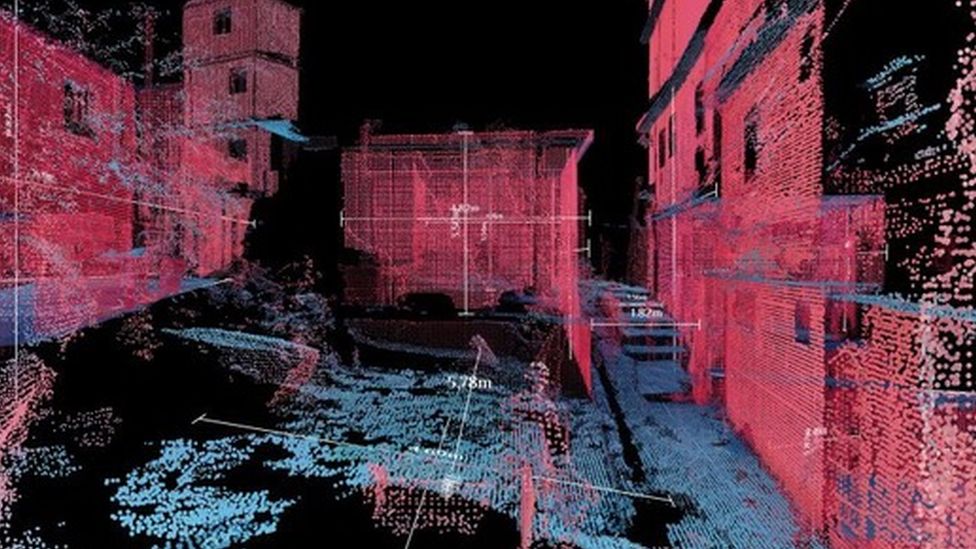

Prof Carlo Ratti and his team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Senseable City Lab recently used handheld Lidar (light detection and ranging) scans in Brazil to map Rio's largest favela, Rocinha. It provided details about the environment that previous maps simply weren't able to achieve,

It will, said Prof Ratti, help identify a range of issues, such as areas prone to landslides, but the clever science is only smart if it works in tandem with real action.

"You can develop maps showing what needs to be fixed but unless it is coupled with someone who is going to fix it, it is all useless," he said.