The record-breaking monsoon rainfall that led to severe flooding in Pakistan this summer was “likely increased” by climate change, a new “rapid-attribution” study finds.

Over June-August 2022, Pakistan received nearly 190% more rain than its 30-year average. On 25 August, the government declared a national emergency after catastrophic flooding that affected more than 33 million people, destroyed 1.7m homes, and led to nearly 1,400 deaths (pdf).

The flooding caused an estimated $30bn (£26bn) in financial losses, with further economic disruption expected in the months to come.

The heavy rainfall experienced in Pakistan this summer has “approximately a 1% chance of happening” in any individual year in today’s climate, according to the study’s authors. Although this estimate “comes with a large range of uncertainty”, they add.

The authors conclude that a five-day period of rainfall that hit the southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan in late August is now about 75% more intense than it would have been had the climate not warmed by 1.2C.

The study also highlights the need for climate resilience in vulnerable communities. One author told a press briefing that “the disaster was a result of vulnerability constructed over a number of years and it shouldn’t be seen historically as the outcome of just one kind of sudden or sporadic weather event”.

Every summer, a shift in wind patterns draws moist air across south Asia, causing heavy rainfall over the region. The monsoon can produce up to three-quarters of Pakistan’s annual rainfall, and often causes localised flooding across the country. In the summer of 2022, record-breaking rainfall brought an unprecedented humanitarian crisis to the country.

Over June-August 2022, Pakistan received nearly 190% more rain than its 30-year average. The southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan were the worst affected – receiving 726% and 590% of their normal August rainfall, respectively.

The heavy rainfall caused widespread flooding, which was exacerbated when the Indus river – which runs the length of the country – burst its banks.

(It has been widely reported that floods covered one third of the country. However, this statistic refers to the proportion of Pakistan’s districts that had declared a “calamity” because of the floods. Nonetheless, estimates suggest 10-12% of the country’s land area was flooded, affecting more than 33 million people – around 15% of the country’s population.)

On 25 August, the government of Pakistan declared a national emergency, calling 66 districts – mainly in Balochistan and Sindh – “calamity hit”. On 30 August, UN secretary general Antonio Guterres launched a $160m appeal to support Pakistan, urging the world to help victims of the country’s “monsoon on steroids”.

The Pakistani people are facing a monsoon on steroids. More than 1000 people have been killed – with millions more lives shattered.

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) August 30, 2022

This colossal crisis requires urgent, collective action to help the Government & people of Pakistan in their hour of need. pic.twitter.com/aVFFy4Irwa

The flood is estimated to have caused more than $30bn in damages. Around 1.7m houses and 18,000 schools were destroyed, while more than 1,460 health facilities were impacted. Meanwhile, almost 800,000 livestock were killed and 2m hectares of crops and orchards were affected – with around $2.3bn of food crops destroyed.

WHO is responding as districts in #Pakistan continue to be affected by unprecedented levels of flooding.

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) August 31, 2022

The impact of the heavy monsoon rains is drastic, affecting 3⃣3⃣ million people in 116 districts across the country.

https://t.co/iUkHk3m2Ig pic.twitter.com/yQ9uwJIoGR

As the rainfall abated, millions of people were left stranded in the open water without shelter or food – leaving them vulnerable to disease. “The timing couldn’t be worse,” the UN warned, “as aid agencies have warned of an uptick in waterborne and deadly diseases”.

Sindh and Balochistan have since seen outbreaks of conditions including cholera, malaria and skin infections. By early September, more than 6.4 million people were “in dire need of humanitarian aid”.

The media and general public were quick to link Pakistan’s floods to climate change. Sherry Rehman – Pakistan’s minister of climate change said:

“I wince when I hear people say these are natural disasters. This is very much the age of the anthropocene: these are man-made disasters.”

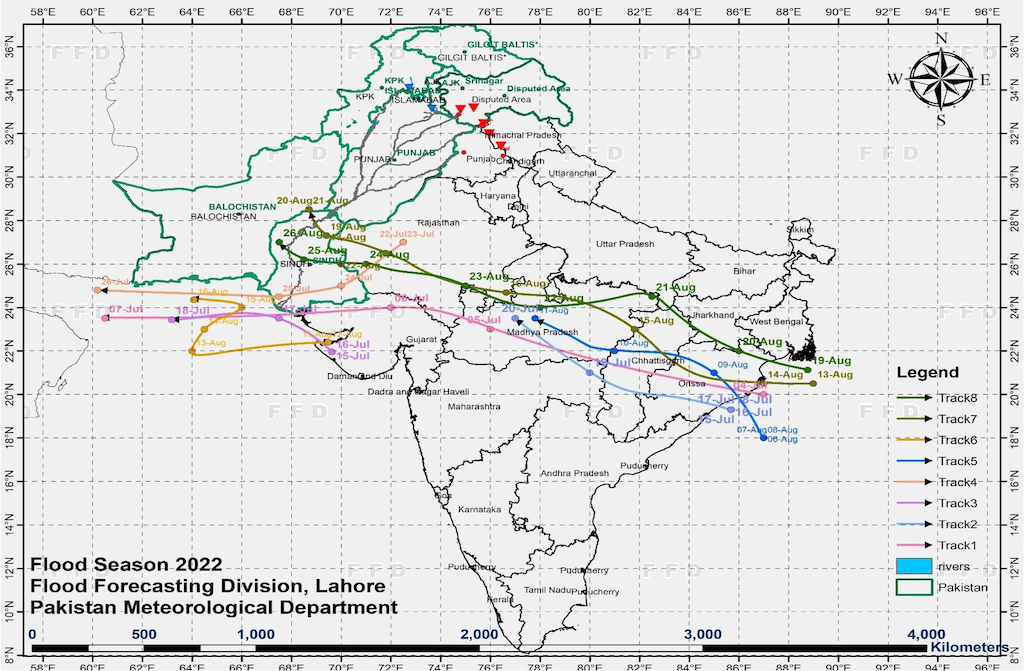

Pakistan’s flooding was mainly caused by prolonged rainfall that hit the country in a series of “monsoonal depressions”, the study says. These depressions – regions of low pressure – travel from the Bay of Bengal over the Indo-Gangetic plains, causing rainfall over the eastern upper Indus basin.

Pakistan was affected by eight depressions in the summer of 2022, although the study notes that it “is usually not affected by monsoon low pressure systems”.

While these depressions usually travel towards the north of the country over the monsoon season, all eight tracks moved over the southern provinces of Sindh and Balochistan this year – drawing heavy rainfall over southern Pakistan.

The map below shows the tracks of the eight monsoon depressions.

Dr Fahad Saeed, the regional lead for south Asia and the Middle East at Climate Analytics, told a press briefing that the heatwave over March and April – which was made 30 times more likely by climate change – “brought the depressions from the Bay of Bengal towards the southern provinces”.

(The heatwave also accelerated melting from the country’s 7,000 glaciers, which feed into the Indus river. However, the study notes that “the relative contribution of glacial meltwater to the flooding is unknown and likely much smaller than the rainfall itself”.)

The intense rainfall was also driven in part by a La Niña event, which caused warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the eastern ocean, providing additional moisture to feed the monsoon depressions, according to the study.

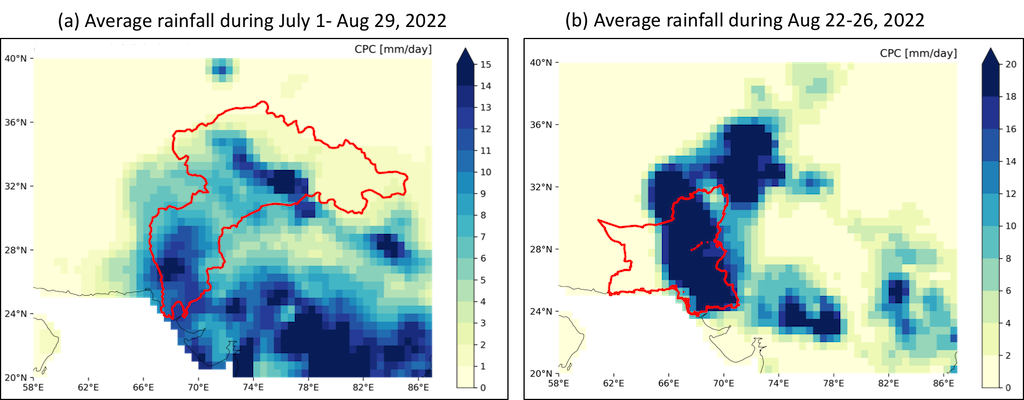

To investigate both the prolonged rainfall and the short, heavy bursts, the scientists defined two regions over different periods of time – the 60-day period of heaviest rainfall over the Indus river basin, and the five-day period of heaviest rainfall in Sindh and Balochistan.

The map below (left) shows the average rainfall in the Indus basin for July and August, where darker blues indicate more intense rainfall. The map on the right shows the highest five-day average seen during summer over the Sindh and Balochistan provinces together (22 to26 August).

The red outlines indicate the areas analysed in the study – the Indus basin and the Sindh and Balochistan provinces.

Attribution is a fast-growing field of climate science that aims to identify the “fingerprint” of climate change on extreme-weather events, such as heatwaves and droughts.

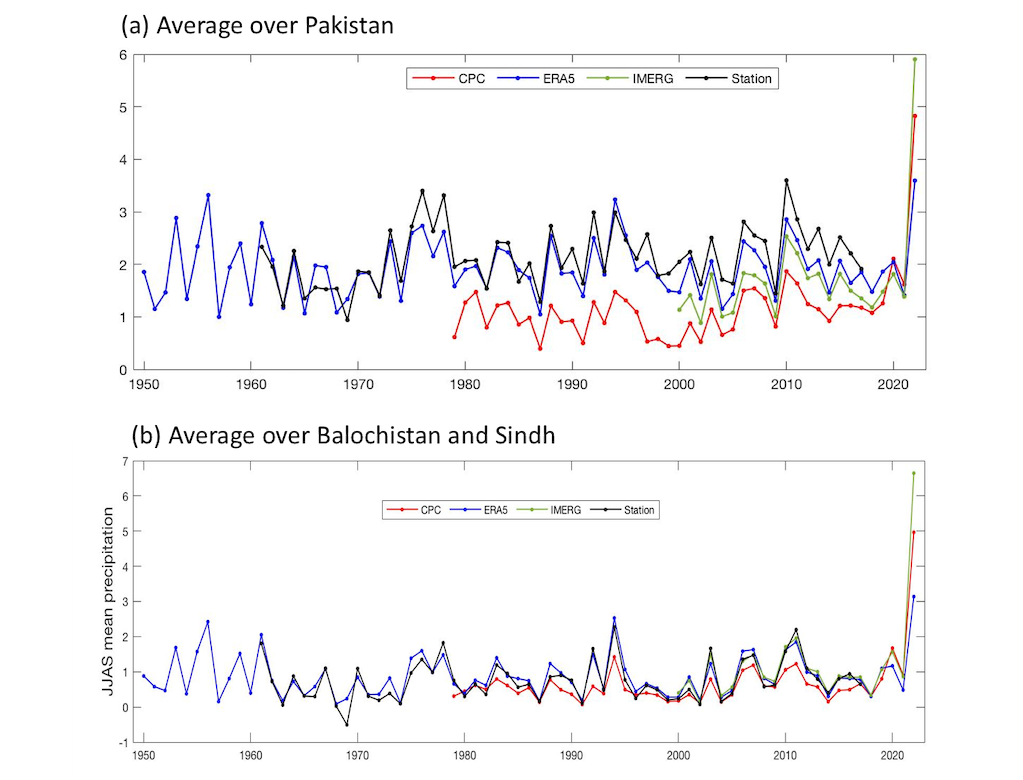

The authors started by putting this summer’s extreme rainfall into its historical context by analysing an observed dataset of rainfall that stretches back for decades.

The Pakistan Meteorological Department provided daily rainfall data over 1961-2017 from 47 stations. The plots below show a timeseries of average rainfall during July to September over the whole of Pakistan (top) and the southern region – made up of Balochistan and Sindh (bottom). The different colours indicate different datasets.

The authors conclude that five-day maximum rainfall over the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan is now about 75% more intense than it would have been had the climate not warmed by 1.2C. Meanwhile, the 60-day rain across the basin is now about 50% more intense.

However, Dr Sjoukje Philip – a researcher at the Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute (KNMI) and author on the study – told the press briefing that there is “large uncertainty” in this conclusion as rainfall in the country is highly variable.

(See Carbon Brief’s guest post for more details on monsoon variability.)

The historical data also shows that both the 60-day and five-day rainfall extremes are likely to happen once every 100 years in today’s climate, the study says.

The authors then combined observational data with climate models to determine the role of climate change on this extreme rainfall. The scientists used models to compare the world as it is to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change in order to distinguish the “signal” of climate change in Pakistan’s rainfall from natural variability.

The authors conclude that climate change “likely increased the intense rainfall” that contributed to the Pakistan flooding.

Prof Friederike Otto – a senior lecturer at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London , and author on the study – told a press conference that there are different conclusions for the five- and 60-day rainfall extremes because the different durations “relate to quite different meteorological phenomena”.

The authors find that for the five-day rainfall extreme, some models suggest climate change could have increased the rainfall intensity by up to 50%. However, they add that “uncertainty remains very large for the 60-day monsoon rainfall”.

Philip noted that it is “very difficult to accurately simulate” rainfall over Pakistan due to its high variability. This means, for example, that “many of the available state-of-the-art climate models struggle to simulate these rainfall characteristics”, and only “a few” of the 31 models available were suitable for use in this study.

The study adds that “for a climate 2C warmer than in pre-industrial times, models suggest that rainfall intensity will significantly increase further for the five-day event”.

(The findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

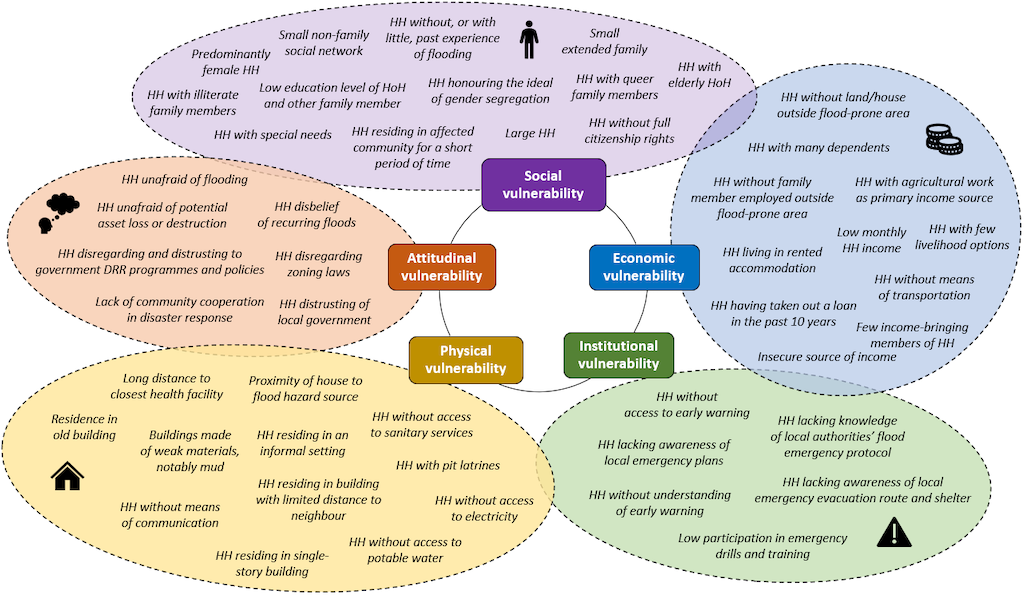

While a mix of physical events was involved in the extreme flooding, the study authors also highlight the role of exposure and vulnerability.

In addition to the proximity of human settlements, infrastructure and agricultural land to flood plains, the factors driving the impacts of the floods include “limited ex-ante [pre-event] risk reduction capacity, an outdated river management system, underlying vulnerabilities driven by poverty, socioeconomic factors that disadvantage women and ongoing political and economic instability”, the study says.

The diagram below provides a visual representation of the household factors (HH) contributing to vulnerability to floods in Pakistan.

Following flooding in 2010 which killed more than 1,700 people (pdf), a report (pdf) commissioned by the Pakistani Supreme Court concluded that, in addition to weather events, “that most damage was caused by dam and barrage-related backwater effects, reduced water and sediment conveyance capacity and multiple failures of irrigation system levees”.

The study notes that Pakistan typically prioritises flood barriers, reservoirs, canals and barrages for flood management – often at the expense of social and environmental considerations.

This has created a number of drainage problems followed by more technical solutions in the Basin, including vulnerability to drainage “failures”, even during non-flood years, the study says. One of the study’s co-authors, Dr Ayesha Siddiqi from Royal Holloway, University of London, told a press briefing:

“The worst damage was not actually from the rainfall itself, but from dam and barrage related issues…The disaster was a result of vulnerability constructed over a number of years and it shouldn’t be seen historically as the outcome of just one kind of sudden or sporadic weather event.”

Beyond these problems, there is also a wider conversation taking place on Pakistan’s engineering priorities, which favour irrigation and power generation with flood control as an afterthought. This needs to be re-considered “in favour of a more decolonial approach”, the study authors write.

The recent flooding has also sparked discussions about climate justice, with Rehman – among others – pointing out that while Pakistan is responsible for less than 1% of total human-produced emissions, it is the 18th most vulnerable country to climate impacts in the world.