Consider this parable from not so long ago, in a galaxy not so far away:

The Kingdom of Nacirema has been engaged in a long and bloody conflict with an age-old foe, and the war has been going badly of late. More and more soldiers suffering from serious wounds and internal bleeding have been arriving at the hospital. But instead of being admitted to the hospital and receiving the operation needed to stem the bleeding — a painful and expensive procedure — the soldiers have been merely receiving blood transfusions and sent back to the front lines with a dose of painkillers.

Well, this is not working out so great, because the enemy is now using more dangerous weapons, which have been sold to them by the Kingdom of Nacirema’s powerful and corrupt corporations. Now even more soldiers are arriving at the hospital with more grievous wounds, requiring ever-larger blood transfusions. The supply of blood is running low, forcing the kingdom to make some tough choices. Because the soldiers’ wounds are now much more serious, not enough blood is available for the transfusions to save all of them. Which soldiers do they save — and which do they let die?

The above story is an allegorical one about the U.S. approach to the new and worsening reality of climate extremes. Despite some recent progress (described in part one of this series), government programs to bolster public infrastructure and move people out of flood zones are drastically underfunded. As a result, when disaster strikes in the form of a major flood, hurricane, or the like, we merely give the equivalent of a blood transfusion to the injured, without stopping the bleeding.

The situation has now reached the point where the government can’t possibly make whole all those wiped out by a disaster, let alone buy out all of the properties that have flooded repeatedly or finance all the beach nourishment projects that could defend coastal property against sea level rise and stronger storms.

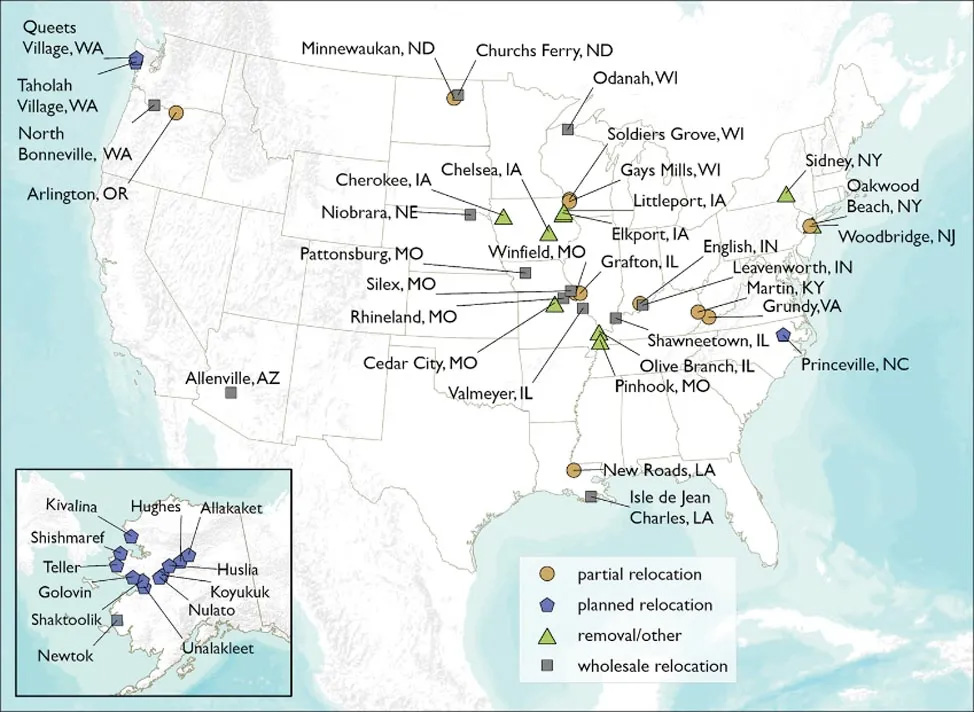

For example, the U.S. Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, meant to help state and local governments better prepare for future disasters, is hugely oversubscribed, despite a recent addition of more funds. And though voluntary home buyouts have helped tens of thousands of families move out of flood-prone homes, millions more remain at risk.

Without a realistic managed-retreat policy, chaotic unmanaged retreat from the coasts and flood plains is more likely to occur, resulting in much greater harm to all affected — and to the economy.

The scope of the problem is vast.

As sea levels rise, $400 billion will be needed by 2040 to build sea walls to protect U.S. communities against floods expected to occur once per year, according to a 2019 study by the Center for Climate Integrity, which used a moderate sea level rise scenario.

Other costs of preparing for sea level rise — including elevating buildings, hardening utilities, telecommunications, transportation systems, and water and sewage infrastructure, plus health care, community preparedness, and environmental protection and remediation, could be five to 10 times higher, or $2-4 trillion. Measures to protect communities from more infrequent floods, such as the one-in-100-year floods that are occurring with increasing regularity, could incur additional costs.

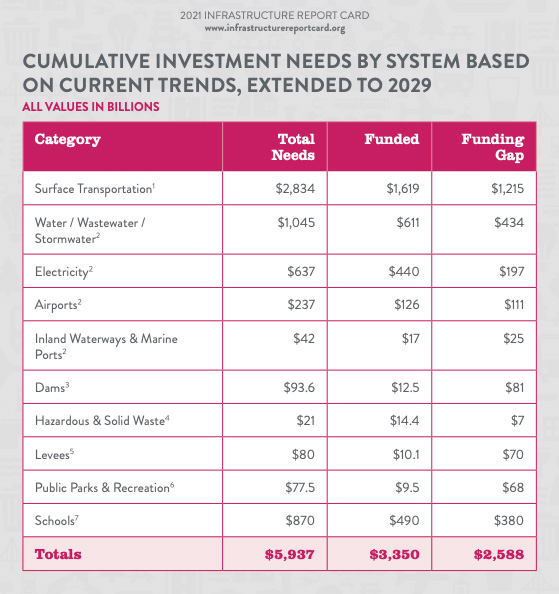

You can add to that bill the $104 billion needed to refurbish the nation’s dams, plus the tens of billions needed to upgrade our levees. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Act of 2021 allocated some $50 billion over five years for climate change resiliency, but a 2021 recommendation from the American Society of Civil Engineers estimated that over $2.5 trillion in unfunded infrastructure upgrades are needed by 2029 in order to attain “B” grades, meaning the infrastructure is safe and reliable.

Many infrastructure upgrades aren’t taking future climate extremes into account.

As sea level rise expert Robert Young of Coastal Carolina University wrote in a 2022 New York Times op-ed, “most of the funded projects are designed to protect existing infrastructure, in most cases with no demands for the recipients to improve long-term planning for disasters or to change patterns of future flood plain development. At the very least, we need to demand that communities accepting public funds for rebuilding or resilience stop putting new infrastructure in harm’s way.”

Just 3-10% of all money spent in the U.S. on climate-related projects is spent on adaptation; the vast majority of this financing comes from the public sector, according to climate adaptation expert Susan Crawford of Harvard. Most of the money spent on climate change — for example, in the landmark Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 — is earmarked for reducing climate pollution. Crawford advocates prioritizing adaptation spending, since every $1 invested in adaptation could yield up to $10 in net economic benefits, according to a 2021 report from the Global Commission on Adaptation.

At the same time, more Americans are moving into risky places. The U.S. population living along the coast at an elevation of 10 meters (33 feet) or lower is expected to grow to 44 million by 2060.

“Discouraging this risky new development will avoid much larger costs of relocating these people and the supporting infrastructure at a future date,” the Coastal Flood Resilience Project writes.

At the moment, taxpayers are subsidizing rebuilding properties in known hazard areas multiple times.

The U.S. National Flood Insurance Program paid out nearly $9 billion to so-called repetitive-loss properties between 1978 and 2012 — nearly 25% of total payments, according to the book “Extreme Cities,” by Ashley Dawson. These payouts were skewed heavily toward rich people.

A managed retreat from risky places, accompanied by the building of new, dense construction in the right places, could reduce taxpayer costs and prepare Americans for the coming climate extremes.

But there is little appetite or incentive for politicians to embrace this solution. For example, cities rely on the municipal bond market to fund city services. But any attempt to implement a managed retreat program from risky areas could hurt their credit rating, because a shrinking population is one less able to repay its debt.

“It is rational for city officials to delay any real effort to move people out of harm’s way, or even to suggest that such a step may ever be necessary,” Crawford wrote.

In his 2024 essay, “The Insurance Apocalypse Conversation America Won’t Have,” journalist Hamilton Nolan is blunt about “how far we are from a genuine public discourse on this topic. We are still mired in the ‘Everything is fine!’ phase, where nervous, sweating politicians with pasted-on smiles beckon you into their doomed states while silently praying that the collapse doesn’t come while they’re still in office.”

Voluntary home buyouts have helped about 45,000 families move out of flood-prone homes over the past 30 years, but this represents a tiny fraction of the millions at risk and is fewer than the number of homes experiencing repeat flood damage and the number of new homes built in flood plains. In her 2023 book, “Charleston: Race, Water, and the Coming Storm,” Crawford of Harvard includes a detailed analysis of the problem, arguing that federal leadership and funding are needed to properly manage retreat from coastal regions:

If FEMA’s buyouts continue at their current pace, they’ll be able to get to about 130,000 more houses over the next 90 years. But there are something like thirteen million Americans in coastal areas who will need buyouts by 2051. FEMA’s current buyout program does not offer any help to people in public housing or renters. What’s needed is a region-wide strategic withdrawal program assisted by coordinated governments at all levels, not a series of one-off buyouts.

Do the math: Only 1% of the needed buyouts may happen under the current system — which also happens to be a cumbersome and unfair process. Buyouts usually take two to five years to finish, and FEMA disproportionately funds buyouts of vulnerable properties in White communities compared to communities of color, since money is allocated based on a cost-benefit analysis that prioritizes more expensive properties. Wealthier communities may also have more resources to influence decision-makers who decide who gets a buyout.

Without a realistic managed-retreat policy, chaotic unmanaged retreat is likely to occur, with plenty of legal challenges, resulting in much greater harm to all affected — and to the economy. As Duke University sea level rise expert Orrin Pilkey and co-authors wrote in their 2016 book, “Retreat From a Rising Sea: Hard Choices in an Age of Climate Change“:

Like it or not, we will retreat from most of the world’s non-urban shorelines in the not very distant future. Our retreat options can be characterized as either difficult or catastrophic. We can plan now and retreat in a strategic and calculated fashion, or we can worry about it later and retreat in tactical disarray in response to devastating storms. In other words, we can walk away methodically, or we can flee in panic.

In their thought-provoking 2021 essay, America’s Next Great Migrations Are Driven by Climate Change, Parag Khanna and Susan Joy Hassolwrite:

In the 21st century, we must shift from coastal to inland, from low to high elevation, and from resource-depleted to resource-rich areas — and we must do so sustainably, for our next habitat may well be our last chance to coexist with nature before there is nothing left to sustain us. To re-sort ourselves according to better latitude and altitude is not to “retreat” but to embrace the future guided by tools that identify topographies better suited for human habitation.

The 2023 U.S. National Climate Assessment, the government’s preeminent report on climate change, recognized the inadequacy of our climate adaptation efforts, saying: “The effects of human-caused climate change are already far-reaching and worsening across every region of the United States … current adaptation efforts and investments areinsufficient to reduce today’s climate-related risks.” The report called for “transformative adaptation,”giving as examples:

In contrast, much of current U.S. climate adaptation efforts are examples of “incremental adaptation, such as spending money to elevate homes above floodwaters. For example, the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law included funds to elevate 19 single-family homes in the Florida Keys.

I love the Keys, but cruel math says that it is not cost-effective to defend the low-lying islands, which are all but certain to be swamped by rising seas in the coming decades. A state-commissioned 2020 report by the Urban Land Institute found that spending about $8 billion to combat sea level rise and storm surges in the Keys would only prevent about $3 billion in damages over the period 2020-2070 — a return of just 41 cents on each dollar spent. In contrast, the study found that in Miami, a similar investment would yield a return of over $9 for each dollar spent.

The 2022 IPCC report affirmed the idea that difficult trade-offs are in store: “Only avoidance and relocation can remove coastal risks for the coming decades, while other measures only delay impacts for a time, have increasing residual risk or perpetuate risk and create ongoing legacy effects and virtually certain property and ecosystem losses.”

As Crawford writes, “This is the American approach in a nutshell: Here’s data. Here are a set of perverse incentives — growth above all, dependence on property tax receipts, perceived need to encourage people to live in risky areas by selling them flood insurance — and broken, patchwork, scattershot legal authorities and programs that make scaled-up, thoughtful relocation just about impossible.”

But U.S. climate adaptation efforts could be significantly reformed with the passage of the bipartisan National Coordination on Adaptation and Resilience for Security Act of 2023, which would create the organizational structure needed to move forward and appoint a chief resilience officer appointed by the president to coordinate climate adaptation efforts. Perhaps the chief resilience officer could take some advice from Crawford’s 2023 book, which has the best proposal I’ve seen on how we should be handling managed retreat from sea level rise:

Imagine gradually making it more expensive to live in dangerous places while simultaneously providing time-limited incentives and subsidies supporting moving away — a multidecade plan, for example, to gradually phase out the mortgages on properties that will be eventually returned to nature, and to subsidize future rent payments if made in higher, drier places. Imagine planning for a multidecade, gradual move, in consultation with each community, to new and welcoming locations well-connected to transit and jobs. Imagine caring for the least well-off among us, ensuring that they have a voice in this planning and choices about whether, when, and how to leave, while firmly setting an endpoint on human habitation in the riskiest places, or, at least, making it clear that these places will be repurposed for other uses. Without this kind of vision, the coming transition will be a cliff rather than a slope, casting millions into sudden misery. Governments at all levels need to understand that the riskiest response of all would be to do nothing, or to act only incrementally, in the face of already accelerating threats that may at any moment abruptly begin accelerating even more quickly, robbing us of our ability to plan. Would you get on an elevator if you knew there was a substantial chance of the cables holding the car snapping just before you reached your floor? Would you have your city’s residents collectively get on that elevator? I don’t think so.

This is part two of a four-part series on U.S. climate change adaptation. Part one looked at a number of recent government adaptation efforts to prepare the U.S. for our new climate. Part three is an essay giving my observations and speculations on how the planetary crisis may play out. Part four describes some personal actions that you can take to prepare for what is coming, including a discussion of where the safest places to live might be.