A group of scientists has proposed a new way to detect climate threats long before they show up as flooded roads, heat-related illnesses or collapsing homes along the North Carolina coast.

The approach comes from researchers at the City University of New York’s Advanced Science Research Center, who published their findings this week in Cell Reports Sustainability. They describe a “Climate BioStress Sentinel System” that would track how climate change is stressing living things — from microbes to trees to people — and use those signals as early warnings of bigger problems ahead.

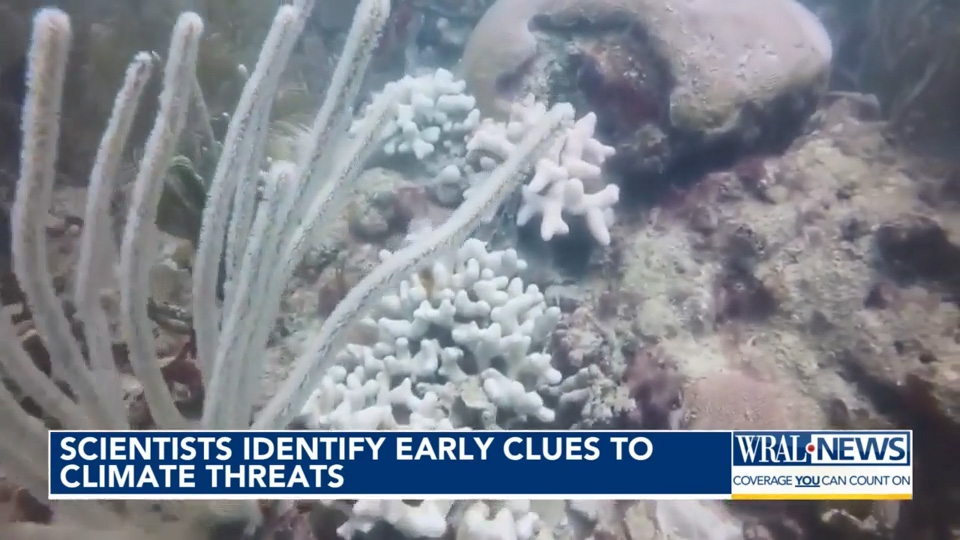

The concept is rooted in a simple idea: life reacts to climate pressure long before humans do. Plants change their chemistry during drought. Microbes shift as water warms. Animals behave differently during heat stress. Even hospital records can reveal early patterns of illness during extreme weather. The research argues that these biological “stress signatures” can act like canaries in the coal mine, offering clues about how climate change is unfolding across entire communities.

Charles Vörösmarty, the study’s lead author, said the goal is to give cities and states real-time tools to anticipate climate impacts rather than respond after they hit.

“Climate change is already affecting every level of life on Earth,” Vörösmarty said. “Those stress signals are measurable, and they can tell us where risks are building.”

North Carolina offers a clear example of the kinds of stress the system aims to track. Raleigh has endured record heat in recent summers, producing spikes in heat-related emergency visits. Eastern North Carolina is seeing more “sunny-day” flooding as sea levels rise. And on the Outer Banks, coastal erosion has pushed 27 homes into the ocean since 2020.

Under the proposed system, those impacts wouldn’t be tracked in isolation. Heat-stressed trees in Raleigh, algae blooms in the Neuse River, and shifting fish behavior along the coast would all be monitored alongside public-health data, weather trends and economic disruptions. Together, the signals would create a clearer picture of which communities are most vulnerable and how climate stress is spreading.

The study argues that cities are particularly sensitive because heat, air pollution, infrastructure gaps and social inequality compound one another. Raleigh’s rapid growth adds another layer, increasing demand on water, energy and emergency services.

The authors envision a system that blends environmental monitoring with public-health and social data. In an extreme heat event, for example, sensors could show which neighborhoods are warming fastest and whether local ecosystems are reacting. Hospitals could identify illness patterns, and mapping tools could show where resources are most needed.

Scientists say the technology already exists. What’s missing is coordination and investment. That gap reflects how most agencies still monitor climate impacts separately, which makes it harder to see how those stresses connect.

“Climate impacts don’t unfold one at a time,” Vörösmarty said. “They cascade.”

The researchers argue that detecting those cascades early could help cities direct cooling resources, prepare for flooding, manage water quality, and protect vulnerable residents.

The proposal is a framework, not a ready-made program. But the authors say the science is strong enough for cities to begin building pilot systems. They emphasize that ignoring climate stress comes with mounting costs — something North Carolina communities are already experiencing after repeated hurricanes, inland flooding and accelerating coastal erosion.